Series 3 episodes

Episode 3

Introduction

Series 2 episodes

Introduction

Series 1 episodes

Introduction

Spread bets and CFDs are complex instruments and come with a high risk of losing money rapidly due to leverage. 67% of retail investor accounts lose money when spread betting and/or trading CFDs with this provider. You should consider whether you understand how spread bets, CFDs, OTC options or any of our other products work and whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

The Artful Trader | Series 2 | Episode 4

The world is an oil painting: What can we learn from energy expert Anas Alhajji

About this episode:

Having grown up on a petrol station, Anas Alhajji feels homesick when he smells gasoline. Now he's one of the most sought-after energy economists and commentators on the oil markets. Anas Alhajji talks to The Artful Trader about the geo-political events that affect oil prices. Will US sanctions be able to stop Iran from exporting oil, and are we heading for another oil crisis? Anas thinks so and has some tips for what traders can do to protect themselves.

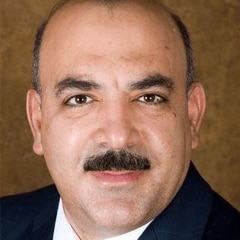

Anas Alhajji

Anas Alhajji is an energy economist who has been watching, researching and writing about the oil market and energy geopolitics and securities for 20 years.

He is the managing partner at Energy Outlook Advisers and was the former chief economist of NGP Energy Capital Management, where he led the firm’s macro-analysis of the energy markets.

Episode 4: The world is an oil painting: What can we learn from energy expert Anas Alhaljji

Anas Alhajji: The oil market is for those who understand volatility, who take advantage of volatility. For all of those who hate risk, basically the oil market is definitely not for them.

Michael McCarthy: From CMC Markets, this is The Artful Trader.

Michael McCarthy: Hi and welcome to The Artful Trader. I'm

Michael McCarthy, Chief Market Strategist at CMC Markets, Asian Pacific. Each episode we'll hear the highs and lows from the industries experts, and hear their journey to mastering the art of the financial markets. If you subscribed to Chaos Theory then a tweet from Donald Trump is like a butterfly flapping its wings. The effect grows in magnitude as it echoes around the globe. But are the oil markets that sensitive to such seemingly small inputs? What are the geopolitical events that will affect the oil price, and are we headed for another oil crisis? Well, our next guest thinks we are and he has some tips for opportunities for traders.

Anas Alhajji is an energy economist who has been watching, researching and writing about the oil markets for 20 years. He's the managing partner at Energy Outlook Advisors and was the former chief economist at NGP Energy Capital Management, where he led the firm's macro analysis of the energy markets. Today from Dallas, Texas, Anas outlines some disturbing news for traders, that the data that we use to analyse the oil and energy market is often wrong. To find out how it's wrong, join us for this deep dive into the world of energy trading.

Michael McCarthy: Anas, thank you very much for joining us for The Artful Trader podcast series. It's a real pleasure to have such an expert in oil markets with us today.

Anas Alhajji: Thank you for having me.

Michael McCarthy: I'd like to start right at the very beginning if we could. What was your childhood like, not just where you grew up but what did you learn about money and success as a child?

Anas Alhajji: I learned that money matters, but only to a certain extent. There are other things in life that at certain points that are more important than money. The story of my family starting with my grandfather basically is a reflection of that. My grandfather has a very interesting story. He was born in Syria. That was at the time when the French occupied Syria, so he left Syria on a ship to Argentina. He got married to his sweetheart, who was the neighbour. They ended up having 12 children. Then when he became very rich, he went back to Syria. He bought a bus. He started a gas station. So I literally grew up on a gas station. So when people smell gasoline, they get sick. I smelled gasoline, I get homesick.

Michael McCarthy: Excellent.

Anas Alhajji: My grandfather died when he was 105 from an accident.

Michael McCarthy: One hundred and five years old.

Anas Alhajji: Yes. And the doctor gave him six months when he was 36. Of course he'd been in every war in modern history and he visited several countries. He spoke five languages. He was rich. He just had it all.

Michael McCarthy: He sounds like an extraordinary man.

Anas Alhajji: The lesson I learned for businesswise basically and even on a personal level, is if I have to think about every issue with a hundred-year-old experience, will I do what I'm doing? And that changed my life. And I've seen my colleagues, whether in college or others basically buy into the short run and literally a few years later lose. So I believe in the thinking of the long run. This long-term view helped me basically see through and avoid the herd mentality and it helped me basically academically and it helped me financially.

Michael McCarthy: Do you think standing apart from the herd is one of the keys to success in markets?

Anas Alhajji: Yes, because many people bought into that herd mentality when they see an event, while those events they look like short-lived, but they have a long-term impact.

Michael McCarthy: And how do you assess the current situation with sanctions being imposed?

Anas Alhajji: Well on, you're talking about Iran of course?

Michael McCarthy: Yes.

Anas Alhajji: Yes. I have a special view on Iran that is different from what people think simply because I've done a lot of research for the last 20 years on sanctions and I have a very long paper on the impact of sanctions. Came up with a theory that sanctions generally speaking fail, but countries continue to impose them, use them simply because of their symbolic value. Looking at sanctions for over a hundred years, they mostly fail to achieve their objective. But since the nineties with the spread of globalisation, we've seen something different and sanctuaries became more effective. And the reason why, because with the globalisation, we globalised the financial system, we globalised the dollar, the US dollar more than ever. That was not the case before. So now sanctions hurt. But as they hurt, it's not necessarily that they achieve their targets.

The issue we have with Iran data. Most analysts, politicians and journalists look at the official data. In my case, I don't look at the official data, I read the official data, but I look deeper and look at other layers of the market and I look at the black market. So what Iran did in the past basically if you look at the data, we have two datasets. One is the official and one is the unofficial, which counts for the black market. The Iranians are, whether they are Iranian people or the Iranian government are smart and they perfected their game and their sanctions. So what they did in the past, they did smuggle oil, they did sell oil under the Iraqi banner as if it was Iraqi oil, not Iranian oil. They did use their oil, for example, in power generation and they exported electricity. So in a sense they exported oil embedded in electricity and they made money.

So there are many ways they can work it out. But now what's different from the previous sanctions is that they signed agreements with neighbouring countries, mostly Turkey and Russia and China to deal with local currencies, so they can avoid using the dollar and the international financial system. They can use cryptocurrency, they can use gold. And we've seen something else that people did not really pay attention to. For example, the Iranians told the Indians and others, look take my oil because at that time in the previous sanctions they can take the oil without breaking the sanctions, because what sanctioned was payment, it wasn't exporting the oil, and probably that's why the Trump administration is emphasizing the oil now, the oil shipments to avoid what happened in the past. So the Iranians were telling the Indians, for example, take my oil, don't pay me now, pay me later. So there are many ways basically to circumvent the sanctions.

The other issue that people forget is markets trump anything else, even religious conviction. If the price is right, people may not be as loyal to their country or to their beliefs or to their standards. So under sanctions, we've seen it all around the world, basically smuggling in other places around the world, we've seen them smuggling diesel and gasoline on the back of donkeys because the price was right, despite the fact that they could be killed at any time. So if the Iranian oil price is discounted heavily, we are only allowing the criminals and the gangs and the smugglers basically to survive and make money.

Michael McCarthy: And that's why sanctions are self-defeating?

Anas Alhajji: Yes. The only way we can do this is if the Trump administration uses the US Navy to block the Gulf. And the reason why I'm saying this, because it happened before. It happened between 1951 and 1953 when the British navy blocked all the shipments out of Iran when Mohammed Mossadegh basically nationalised the assets of the Iranian Anglo Oil Company. So if we are talking about historical evidence, historical evidence shows the only way you can block Iranian oil is to use a complete military blockade. And we know that this might not happen this time.

Michael McCarthy: And yet a number of times this year we've seen when sanctions are announced or imposed we've seen oil markets react. Why do they react if the reality is that the sanctions will be worked around?

Anas Alhajji: Well this is a very good point because it seems markets react to what people believe in regardless of reality. So if people believe that there will be a large decline in exports, then prices will go up regardless until the physical market hits people on the head and realise that we have plenty of oil.

Michael McCarthy: So for those traders who want to stand apart from the herd, what should they be watching in oil markets?

Anas Alhajji: Well, let me kind of focus on one side. People who are bullish on oil are focusing on the supply side and saying, look we don't have enough supplies coming to the market. We have a lot of disruptions. We have a very small spare capacity left, so if we lose more oil from Iran or Libya or Venezuela, we cannot compensate for it. Here is the problem with the thought. The problem is yes, that will increase prices and that makes people bullish but not that bullish, and the reason why because they are forgetting the demand side of the equation. At current exchange rates, as you know, the dollar has been going up relative to other currencies, the currencies of emerging markets have been collapsing, so at current exchange rates, current economic growth, current government expenditures, current interest rates, if oil prices go to a hundred, we will have a serious problem worldwide because we might end up with a recession or a very slow economic growth. The reason why is that the higher dollar makes oil very expensive in emerging economies where most of the growth and demand is.

Michael McCarthy: Oh I see.

Anas Alhajji: So even if oil prices do not move up, just the higher dollar makes it more expensive. So if oil prices move toward $100 because of a crisis in Iran or Venezuela or other places, oil is going to be very expensive in emerging economies and that's going to slow demand significantly. So what I'll be watching to reply to your question, is really exchange rates. I think exchange rates are the most important thing to watch aside from politics for the remaining of 2018.

Michael McCarthy: Right. So given that we're expecting further strengthen from the US dollar, are we heading towards a global crisis driven by oil?

Anas Alhajji: I mean definitely because again with oil we have the issue of what is the price of oil inside those countries where those currencies are declining. So if you look at a country like Turkey, you look at a country like India, Brazil, Argentina, oil is becoming more expensive.

Michael McCarthy: More from Anas Alhajji in a moment. This is The Artful Trader, uncovering the highs and the lows to mastering the art of the financial markets. In markets, pain is a great teacher, so what does it feel like to lose everything. In case you missed it, The Artful Trader spoke with the famous or infamous Nick Leeson, the rogue trader who took down a two centuries old merchant bank. He opens up about the painful lessons he learned about himself and trading while in prison.

Nick Leeson: It's definitely the most embarrassing period in my life. But if you can go through that transition where you've really taken yourself apart, you can then build yourself back up and you can move forward, and you know my childhood was pretty much like everybody else's I would imagine. You know the difference between right and wrong, and this was wrong.

Michael McCarthy: You can hear all of our interviews at theartfultraderspodcast.com or wherever you get your favourite podcasts. Now, back to my chat with

Anas Alhajji in Dallas, Texas.

Michael McCarthy: Anas traders often have late night discussions about the trading day and current market conditions. One of the most remarkable aspects of markets over the last couple of years is extraordinarily low volatility. Whether we look at indices or foreign exchange, the markets are at historic lows when it comes to volatility, but the key exception has been the oil market. Why are oil markets and energy markets so much more volatile than other markets?

Anas Alhajji: Well, generally speaking, if you look at the history of the oil industry, most of the expenditures basically are upfront. Think about an offshore development. You have to put hundreds of millions of dollars for that offshore development before even you produce a single barrel of oil. Then by the time you produce it, you don't know whether prices are going to be low or high, but you end up basically producing no matter what. Even if oil is at $10 and you make those products basically based on 30-year stream of revenues rather than just one or two years. And as a result when you end up with several projects coming online at the same time, regardless of the price basically, they will flood the market.

So we ended up with a situation where when prices go up, everyone will go and invest and those were the lead time and everything else, and then they would come online when prices are not that high, and we end up with that volatility. So the industry and policymakers realised this a long time ago. So we ended up with the, what we call the seven sisters. The seven sisters, these are seven oil companies, dominated the oil industry for a very long time in the twenties and thirties and forties, and they work like a cartel, and they literally manage the market in a way where we had zero volatility for a very long time. So if we have a chart you can imagine that we have a lot of volatilities in the twenties and before the twenties. And then we have this just straight line for decades for the price.

And then, as the antitrust laws and everything else worked their magic etcetera, and broke up those companies, and here comes the sixties, early seventies, the oil companies because of nationalization in the Middle East, in Venezuela and Mexico, other places, they were forced out so they lost control of upstream and OPEC basically became a player. But OPEC was not an integrated producer that controls the whole industrial like it did, or like we've seen with the seven sisters. So they control only one segment of the industry. So they couldn't control the market like the seven sisters and volatility basically increased. And until today basically OPEC has no control of the market, they can influence the market and it's not even OPEC that influences the market, it's really Saudi Arabia that influences the market, but they cannot control it, and therefore we end up with this kind of strong volatility in the market because we don't have an effective manager to manage a commodity where you have this massive investment that needs to be put at front, and once you produce, you produce no matter what the price is.

Michael McCarthy: Okay, so the long lead times in supply-side responses mean that that volatility is likely to continue?

Anas Alhajji: Correct.

Michael McCarthy: So how would you recommend traders approach the energy markets? Clearly volatility is a traders friend when markets are moving, there's potential opportunities. But of course that comes at much higher risk. What can traders do to take advantage of this volatility?

Anas Alhajji: Well, if you are an investor of course you have to be knowledgeable of the industry and you have to know all sides. If you don't know basically probably you need to go the private equity way because those guys know what they are doing. And if you are a trader, basically you trade levels, you don't trade from level to level because that will help you with reducing the risk. But generally speaking, for all of those who hate risk, basically the oil market is definitely not for them. The oil market is for those who understand volatility, who take advantage of volatility, because it's not only that investment and the lag time and the production, etc. etc. there are other issues.

The oil industry has one of the worst data you can imagine among various industries. We have serious problems with data and information. And the first problem we have right now, this is kind of an emerging problem with the spread of social media, with the spread of information technology, we have a big issue with circular information. What that means is, assume a journalist in Indonesia writes a small story for the Nikkei Journal or some other newspaper in Asia, and he will say something like, 'according to some Chinese sources, this, this, this', so just one line piece of news. And then by the next day basically some newspapers or some websites will pick it up in the United States, and then some traders basically they have their own columns and articles and they start writing about it based on that piece of news. And then by the end of the month we'll see the international energy agency or OPEC basically writing a report on it and then the media will start citing the international energy agency or OPEC as saying it. And if you are doing research on it two months later, you go to the web and you'll find out that you have 2000 references, and you say, 'wow, this must be a very important issue'. So you start doing your research only to find out that all of them have the origin of one story that is an unconfirmed story.

Michael McCarthy: It would be funny if it wasn't so serious?

Anas Alhajji: I collected a large number of stories like this in the last year or so where you ended up with 2000 stories on the web and it comes only from one source, but people think it's coming from all kinds of sources. So what happened is, although these things are not real, but if traders believe in them, they become reality. And the other source of the problem that no one is paying attention to, we and all those organisations and banks hire the best analysts, pay them the top dollars to analyse the oil market, but for those who enter the data, we hire some young people with minimum wage to enter the data. And guess what? We have serious problem with data entry. I collected probably at least 15 incidents of data entry mistakes among the most significant organisations and banks in the oil industry where either they enter the data into the wrong column, they enter the wrong data, they have the wrong decimal, etc etc. and the data is completely useless. Yet, when analysts use it, they think that's the data. So we have serious problems with data entry and that is causing another source of volatility.

Michael McCarthy: So in real time the information is often more misleading than leading.

Anas Alhajji: Correct. And the irony is the industry has enough money to invest in information and data, but for some reason this is not the way it's going.

Michael McCarthy: Looking at the bigger picture, it's often sort of put out there that if oil prices go up, it has a drag effect on the economy. On the other hand, we also regularly hear that rising oil prices are a sign of a healthy economy. What do you think of the relationship between oil prices and the broader economies?

Anas Alhajji: This is a very interesting question, here is why. Historically speaking, the conventional wisdom that higher prices hurt economic growth in the industrial countries and therefore they are not good. So industrial countries, they did their best by creating the International Energy Agency and creating policies to kind of try to lower their dependence on oil and to keep oil prices low. That's the conventional wisdom. But if you look at what happened in the last few years as the US added more than 5 million barrels a day from Shale and the US becoming literally very soon, the largest oil producer in the world, all of a sudden higher oil prices basically are good. They stimulate economy, they create jobs. The taxes collected from the oil industry during a boom basically is massive. And all of that basically contribute to economic growth. So lower oil prices now after the shale revolution is not good. So the conventional wisdom is changing.

On the other side, I strongly believe that the conventional wisdom is wrong, and here is why. Because people who say every recession was preceded by a period of high oil prices, if you look at the data, every recession was preceded by a period of a decreasing government expenditures, higher interest rates, for example, or higher taxes. Every one. So which one really caused the recession? It is very clear to me that oil prices hit the economy only in combination with other macro variables. To prove the point look at oil prices and economic growth between 2003 and early 2008. Oil prices continued to go up and they exceeded a hundred and economic growth in the US, in OECD, in China and India continued to go up, incomes continued to go up, employment continued to go up. So it is very clear that it's a combination of macro variables with oil prices that make oil prices basically hit the economy or help the economy.

Michael McCarthy: The oil price changes are a symptom of changes in the economy, not a course?

Anas Alhajji: Correct. So if we have the opposite, we are going to end up with a crisis. So I think that conventional wisdom is not correct. At the same time, even if it's correct, we have a change in conventional wisdom after the shale revolution because of the massive contribution of the shale revolution to the economy.

Michael McCarthy: Absolutely, and that big change to where from the US's previous stance where it was always an energy importer to now having the capability to export, clearly is having an impact on markets. One of the things that traders are focused in on is the fact that Brent and West Texas used to trade essentially in lockstep and yet these days there's a hugely variable spread between these two essentially identical grades of oil. What would you attribute that change to?

Anas Alhajji: Correct. The IEA, OPEC, EIA and other banks and other oil companies basically forecast a major increase in shale oil production in the United States and they think it's going to flood the market in the coming years. Here is the problem with that? The same organizations believe that demand will go up, but only for certain petroleum products that are on the heavier side, while shale is light, sweet, crude, and you cannot get a lot of the heavier side of products from the lighter crudes. What that means is if the demand in the future is coming from the heavier side, while the production is on the lighter side, we are going to have a problem. The reason why the United States government lifted the ban on exports in 2015, because we were going to hit a refining wall in the United States where US refiners cannot take any more of that quality, so they were asking the government to allow exports, finally it did, so we are literally kicking the can down the road and we are sending it to other countries.

Here is the irony, US refiners are the largest in terms of percentage, they are the largest producers of gasoline which we can produce from NAFTA from lighter products. The rest of the world basically does not produce that much gasoline, so their capabilities of taking light crude is way lower. So the rest of the world is going to hit that refining wall too. So the first point is we are going to see a mismatch between production and refining capabilities, and then the second problem is we are going to see mismatch in crude quality between what's going to be demanded and what's being produced. Now people might say, 'oh, we can blend the crude and produce whatever we want to'. That's a serious problem because blending is not like the original, and blending causes many problems for refiners. So not all blends basically work for refiners, especially when you blend light crude coming from the Eagle Ford, for example, in South Texas with Canadian heavy. You end up with a lot of impurities and other things in it, and refiners do not like that because it just cost them more. They liked the original crudes, so we have problem with mismatch between what's being produced and refining capabilities. Refiners are not going to invest to handle the lighter crude because the future demand is on the heavier side, and on the other side blending is not going to solve the problem. That's why if you look at the new, Nymex new WTI contract that will start on January 1st, 2019, it's way tighter than what it is now, and that's going to cause a major problem in the United States because some blends are not going to be acceptable anymore as WTI. So the bottom line, as I say in my twitter feed all the time, crude quality matters.

Michael McCarthy: In all areas of life, not just energy markets. And I certainly take your point to about the regional nature of oil markets. As an example, what the Americans call gasoline in other parts of the world is known as petrol. Just one example of that regionalism, but I'd like to get your thoughts on what the future looks like. I mean, are we in a state of energy transition?

Anas Alhajji: No. Basically I'm going to take this energy transition on directly because the history of humanity is the history of energy transition. The shale revolution reminded us of two lessons. Never say never and the only constant is change. But the shale revolution taught us a new lesson which is that change is happening faster and faster and faster. Because of that speed, people are talking about energy transition, because they are seeing it before their eyes and say, well, this never happened before. No, it happened, it's just happening faster. But talking about the future, here is the problem we are facing in the future. Aside from the fact that shale is not going to deliver because of quality issues, so we have problems on the supply side, on the demand side, we have two major problems.

The number one, the major forecasters are talking about a major decline in demand because of fuel economy. We are talking about engine efficiency here. We are not talking about electric cars. We're talking just about engine efficiency that the engine use of gasoline is going to decline substantially. Well, all the evidence in recent years basically contradicts that. We reach, technology is already maxed out, unless we get the new technology that Aramco, Saudi Aramco is talking about, with absent that technology, we are not going to have that efficiency. That's number one.

Number two, for some reason everyone wrote off Europe and they expect Europe oil consumption to decline like a rock in the next 25 years. Here is the problem. They've been revising demand in Europe every quarter since 2014 and the difference between their forecast and the revision is very large. Why? Why have they been revising it up and all of a sudden next year it's going to go down. It seemed that there is a clear misunderstanding of the relationship between economic growth in Europe and oil demand. Here is the other missing puzzle when it comes to Europe. People talk about population growth. They say, well, Europe population is going down. It's ageing, etc. Well, what about those millions of immigrants who migrated to Europe in the last 10 years and we know for a fact from all evidence around the world that the first generation immigrants, they have higher birth rate than the following generation. So I think Europe is going to surprise on the upside and therefore demand for in the future is going to be way higher than estimates. So demand is going to be way higher, supply, shale is not going to deliver because it's going to limit itself because only shale is going to kill shale growth, and then we are going to end up with energy crisis because oil production at certain times in the next few years is not going to be able to meet demand.

Michael McCarthy: Thank you very much for sharing your insights with this. This will be invaluable to our customers and to the broader listening audience of The Artful Trader podcast, so I really appreciate your time tonight.

Anas Alhajji: You're welcome, Michael and your crew. Thank you very much.

Michael McCarthy: That was Anas Alhajji speaking to us from Dallas, Texas. For more information about Anas, you can go to his website, see the show notes for the link. For previous episodes of The Artful Trader, and more information about CMC Markets head to our website theartfultraderpodcast.com where new and existing clients can also access some limited time offers. Or you can subscribe to The Artful Trader on your favourite podcast app. The Artful Trader is an original podcast series by CMC Markets, a global leader in online trading. The information in this podcast is general in nature and does not speak to your personal financial situation. I'm Michael McCarthy. Thanks for listening to The Artful Trader.

Please select a country