Bonds vs Stocks - Understanding your investment options for UK traders

Whether to invest in stocks or bonds is a key decision for UK investors and traders. Although there are a range of other assets you can invest in, these two assets are the cornerstones of most investment portfolios. In fact, any assets that aren’t stocks or bonds are sometimes collectively referred to as ‘alternative assets’.

As asset classes, stocks and bonds are quite distinct from one another and can serve very different purposes in a portfolio. Hence, it’s important to understand how these investments work, when each might be more suitable, and how to use them together to create a more robust and diversified portfolio.

What’s the difference between stocks and bonds?

What exactly am I buying when I purchase stocks?

When you buy the stock of a listed company, you're purchasing shares in that company, making you a partial owner of that business, which brings with it several benefits and factors to consider, such as:

Legal ownership

Share capital

Dilution

Dividends

Voting rights

Legal ownership: When you purchase stocks, you become a shareholder, which means you are the legal owner of a small fraction of that business.

Share capital: Exactly how much of that business you’ll own will depend on the number of shares the company has issued and how many of those shares you’ve bought.

Dilution: If a company that you have shares in decides to issue additional shares in order to raise more money, your share capital will decrease even though you still own the same number of shares.

Dividends: As a shareholder, you're entitled to receive dividend payments if and when the company distributes profits to shareholders. Not all companies pay dividends.

Voting rights: When you invest in a company by buying their shares, you won’t have the same rights to determine day-to-day business decisions as that company’s founders and directors will have, but your shares often do give you ‘voting rights’ - usually one vote per share.

When I buy a bond, what am I lending and to whom?

When you buy a bond, you're lending money to the bond issuer, and in most cases that issuer will either be a national government, a municipal government, or a company.

Government bonds: When you buy government bonds, you're lending money directly to national governments to fund their operations, infrastructure projects, or refinance existing debt. In the UK, these are called gilts and are issued by HM Treasury, while in the US, they're known as Treasury bonds and are issued by the US Treasury.

Municipal bonds: Municipal bonds can be issued by local government authorities, councils, or public sector agencies to fund local infrastructure projects, such as schools, hospitals, roads, or public transportation systems. In the UK, these might be issued by city councils or regional authorities through the UK Municipal Bonds Agency (UKMBA), but that’s fairly rare. Municipal bonds are much more common in countries like the US than they are in the UK.

Corporate bonds: Corporate bonds involve lending money to individual companies rather than governments. Companies issue bonds to raise capital for various purposes, including business expansion, equipment purchases, acquisitions, or refinancing their existing debt. Because companies have a higher risk of financial difficulty than stable governments, corporate bonds offer higher interest rates to compensate investors for taking on additional risk.

Understanding trading risks

What are the risks of trading stocks?

When it comes to stock trading, the main types of risks investors are likely to face are:

Market risk

In simple terms, market risk represents the risk that the entire stock market will decline due to factors like a recession, a spike in interest rates, or major geopolitical events, all of which can impact the entire market. For instance, when the FTSE 100 falls sharply, most individual stocks tend to fall with it, regardless of how well the underlying companies are performing. Even if you own shares in a profitable, well-managed company, the risk is that your investment can still lose value during these market downturns.

Unsystematic risk

Unsystematic risks arise from factors affecting individual companies, rather than whole markets. Whether these factors are poor management decisions, product recalls, the loss of major customers, accounting scandals, or greater competition in their key markets, since they don’t affect the whole market, these risks can be mitigated through diversification, which is why they’re sometimes called ‘diversifiable risks’.

Volatility risk

Volatility risk relates to the risk that a particular share’s price experiences sudden volatility.

In some cases, individual stock prices can swing dramatically from day to day, sometimes moving by as much as 5% or 10% (or more) in a single trading session without any fundamental change to the company's prospects and without the overall market experiencing that same degree of volatility.

Some stocks are more volatile than others - technology companies and smaller growth stocks tend to experience wider price swings than established utility or consumer goods companies, for instance. Traders can measure this volatility using a metric known as ‘beta’, where stocks with a beta above 1.0 are more volatile than the overall market, and those with a beta below 1.0 are less volatile than the market.

Potential for total loss

In contrast to bonds, which often retain some of their value even if a bond issuer defaults on its interest payments, the value of a stock can potentially fall to zero if that company goes bankrupt. Since shareholders are last in the line of creditors if a company is liquidated, there’s the risk that you might lose your whole investment if you own stock in a company that goes bust.

What are the risks of trading bonds?

Bond trading comes with risks, too, but they’re a little different from stock trading risks. With bond trading, the main risks you’ll face are:

Interest rate risk

Interest rate risk is the single biggest risk for bondholders. When interest rates rise, existing bond prices fall because new bonds offer higher yields, making older bonds less attractive.

If you need to sell a bond before maturity during a period of rising rates, you might receive less than you paid for it. Longer-term bonds are more sensitive to interest rate changes than shorter-term bonds, so a 30-year government bond will fluctuate more in price than a 2-year bond when rates change. That’s why interest rate risk is sometimes referred to as duration risk.

Credit risk (default risk)

Credit risk is sometimes called ‘default risk’ because it relates to the possibility that the bond issuer might default on their interest payments or fail to repay the principal.

Government bonds from stable countries like the UK usually have very low credit risk, but corporate bonds can have a much higher risk of default. Credit rating agencies like Moody's and S&P assess this credit risk, with AAA-rated bonds being the safest and junk bonds carrying much higher default risk.

Inflation risk

Inflation erodes the purchasing power of fixed bond payments over time, which is particularly relevant for bonds with long maturities..

For example, if you own a bond that pays annual interest of 3%, but inflation is currently 4%, then your interest payments will gradually lose purchasing power each year.

Since long-dated bonds will mean you're locked into fixed payments for many years, inflation risk is an important consideration for bonds with long maturities.

Liquidity risk

Liquidity risk can pose a problem if an investor struggles to find a buyer for an investment asset that they want to sell, and this type of risk is particularly significant for bonds because bonds don’t trade on centralised exchanges like stocks do.

Major government bonds like gilts and Treasuries rarely experience liquidity issues, but liquidity risk is a very real risk factor with corporate bonds.

How do stock and bond markets work?

To make informed decisions about your overall investment strategy and individual trades, you’ll need to know how stock markets and bond markets work, and how much you’ll pay to buy and sell these particular assets.

Are stocks easier to trade than bonds?

In many cases, trading stocks and shares is easier and more accessible than trading bonds, even though stocks offer many more investment options to choose from.

Live prices: Stock trading platforms, financial websites, and finance apps can show investors and traders the ask (buying price) and bid (selling price) for any share in real time. This transparency means you always know exactly what price you'll pay or receive when you place an order. The constant flow of price information helps ensure fair pricing and allows you to make informed decisions about when to buy or sell.

Tight spreads: The difference between the ask price and bid price is usually very small for major stocks, possibly as low as 0.01 to 0.05% of the stock price. For a £100 stock, this might mean paying £100.05 to buy but only receiving £99.95 if you sell immediately. This tight spread is possible because so many people are trading the same stocks, creating high liquidity.

Instant execution: When you click buy on a major stock during market hours, you typically own those shares within seconds. Electronic trading systems match your order with someone willing to sell at your price, and the transaction completes almost immediately. This speed and certainty make stocks very accessible for active traders, provided trades aren’t placed outside market trading hours.

Easy to exit: Your shares can usually be sold very easily, particularly if you own shares in major companies that have high liquidity. This liquidity means you're rarely stuck holding stocks you want to sell. The one caveat is if you’ve invested in ‘penny stocks’ with lower liquidity levels, particularly if those penny stocks aren’t trading on major stock exchanges - in that case, you might have to wait a little longer to find a buyer for those shares.

Is trading bonds harder than trading stocks?

Hidden prices: In contrast to stocks and shares, it’s less straightforward to see live bond prices on standard platforms. Bond dealers will often only provide quotes when you specifically ask for them, and these quotes can vary between different dealers. This lack of price transparency makes it harder to know if you're getting a good deal on your bond trade, and it also means you’ll probably have to do more research before you buy or sell a bond.

Wide spreads: The difference between buying and selling prices for bonds is much bigger than for stocks, possibly as much as 0.25% to 1.0%, or even wider for less liquid bonds.

Dealer network: When you buy bonds, you're typically buying from banks, brokers, or other financial institutions rather than directly from other individual investors. These dealers make money from the spread between what they pay to acquire bonds and what they charge you to buy them, which can work well for large institutional investors but often means higher costs for individual traders.

What are the costs of trading and investing in stocks and bonds?

In most cases, it will cost more to buy or sell bonds than it would cost to trade shares of the same value. These higher costs are largely due to a much bigger spread between the bid and ask price on bonds, although broker commission can also play a role.

What are the trading costs for stocks and bonds?

What are the investing costs for stocks and bonds?

Stocks and Bonds trading V Investing costs

Understanding market conditions for stocks and bonds

Government bonds are often seen as ‘safe havens’ while stocks are considered riskier investments, which means share prices and bond prices often move in opposite directions.

This inverse relationship means traders who trade both of these asset classes can often find investment opportunities no matter what the market conditions are, because when stocks are struggling, bonds might be rallying, and vice versa.

Differences in market conditions between stocks and bonds

How do bonds and stocks perform in different economic cycles?

Different phases of the economic cycle have historically created distinct market environments. Understanding these patterns may help traders and investors better comprehend market dynamics, though past patterns do not guarantee future performance.

Economic recession

Stocks: During a recession, companies often experience declining revenue, which can result in a decline in their share price.

Bonds: Because bonds are often seen as ‘safe havens’, bonds often outperform during times of economic uncertainty or worries about a looming recession. When investors become risk-averse, they often move money from volatile stocks into the perceived safety of government bonds, particularly UK gilts or US T-Bills.

Real examples:

2008 financial crisis: The FTSE 100 fell by 31%, while the price of government bonds gained more than 20%

2020 Covid crash: The FTSE 100 fell by 34% (March), while the price of bonds gained 8%.

Disclaimer: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results

Economic early recovery

When a recession begins to tail off and the economy starts to show signs of improvement,

Stocks: Investors who previously sold their equity holdings may begin to invest in stocks again, triggering a rebound in the stock market. Corporate profits may begin to recover during this phase as well, and this can encourage further demand for stocks.

Bonds: On the other hand, interest rates aren’t likely to have been hiked again yet, so newly issued bonds may be less appealing to investors than recovering stocks.

Real examples:

2009-2010: Stocks gained +23%, bonds gained +6%

2020-2021: Stocks gained +27%, bonds gained +7%

Disclaimer: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results

Economic expansion

During a phase of significant economic growth:

Stocks: Stock markets typically perform well during periods of economic growth, so when GDP is rising, unemployment is falling, and consumer confidence is high, the overall market is likely to rise. Those periods of economic growth often allow companies to make more money, which means their share price will rise, but there are also some types of stocks that might do well during a weaker economy or even a recession.

Bonds: Interest rates often rise during a strong economy, which will make existing bonds less attractive, and inflation will often rise too, undermining the purchasing power of a bond’s interest payments.

Real examples:

2010-2018: Stocks averaged +15% per year, bonds averaged +3%

1990s Bull Market: Stocks gained +18% annually, bonds gained +7%

Disclaimer: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results

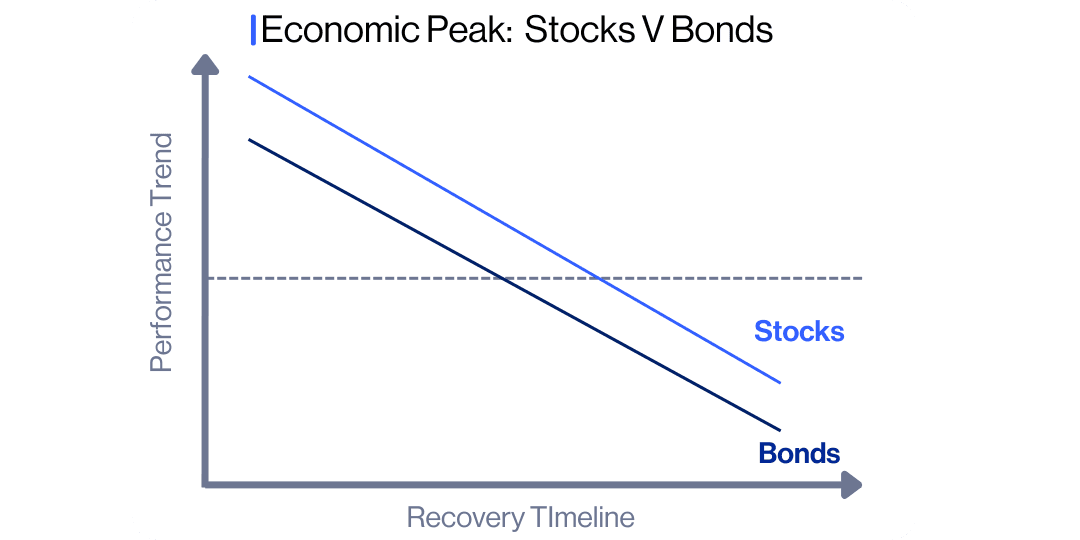

Economic peak

When economic growth is reaching a peak, the inverse relationship between stocks and bonds can often break down, with high inflation, high interest rates and economic uncertainty conspiring to drive the value of both stocks and bonds downwards. It’s this downward push that will eventually lead to the cycle beginning all over again.

Real examples:

1970s: Stocks flat for decade, bonds lost purchasing power

2022: Stocks fell -18%, bonds fell -13% (rare for both to fall together)

Disclaimer: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results

Bonds vs equities: trading both

Many successful traders don't limit themselves to just stocks or just bonds; they use both asset classes strategically based on market conditions and trading opportunities.

“Pairs trading” involves simultaneously buying one asset while selling another to profit from relative price movements. Using CFDs for these trades allows traders to take both long and short positions across stocks and bonds without owning the underlying assets. This flexibility offers traders the possibility of profiting from both rising and falling markets in either asset class.

What does this mean for different trading styles

Day traders, scalper, swing traders (buying and/or selling frequently)

Stocks: Typically feature lower transaction costs and faster execution

Bonds: Generally involve higher trading costs, which may impact frequent trading strategies

Position traders (holding for months/years)

Stocks: Usually offer straightforward entry and exit processes

Bonds: May involve higher initial costs, but are designed for longer-term holding periods

Please consider your circumstances and seek independent advice if needed before making any investment decisions.

CFD Trading: Stocks vs Bonds

What are stock CFDs?

Stocks represent a share of the equity in a listed company, so when you trade stock CFDs you're speculating on the changing share price of that company.

Whether you choose to buy those stocks outright or use financial derivatives like CFDs to speculate on the changing value of those stocks, your return will be directly linked to that company’s share price, which is impacted by a wider range of factors such as:

New product launches by that company or its competitors

The appointment of a new CEO or other key executive appointments

Macroeconomic changes that affect the countries the company operates in

Sociopolitical changes that affect the company, either individually or because of the industry it is in

Regulatory announcements that might affect how that company operates.

Because so many things can affect a company’s share price, Stock CFDs often offer many more trading opportunities than bonds.

What are bond CFDs?

Bonds are loans to governments or companies, so when you trade bond CFDs, you're speculating on the possibility of interest rate changes and changes in creditworthiness, and how those changes would affect the value of the bonds.

There are several reasons traders might favour bond CFDs, including:

Macro trading opportunities in the run-up to central bank interest rate decisions

Interest rate sensitivity can sometimes create more predictable price movements

Bonds are often negatively correlated with stocks during market turmoil

Bond CFDs can offer higher leverage options than stock CFDs.

Example:

When the Bank of England hints at an interest rate cut, the price of UK gilts usually rises. Although this price movement might only amount to 1% or 2%, if a trader employed leverage on their bond positions, then the potential returns (or losses) on their margin could be significantly higher.

How does leverage change bonds vs stocks' risk profiles?

Leverage fundamentally alters the risk-return dynamics of both bonds and stocks, but the effects manifest differently due to their distinct characteristics.

Stock leverage risk

Stocks already exhibit higher volatility than bonds, so leverage amplifies these price swings. However, stocks have historically provided higher long-term returns, potentially making leverage more sustainable over time. The key difference is that stock leverage amplifies both higher baseline volatility and higher expected returns.

Bond leverage risk

Leverage amplifies bonds' inherent interest rate sensitivity dramatically. A 2% decline in bond prices becomes a 20% loss with 10:1 leverage. Since bonds typically move 1-3% daily, leverage can quickly turn modest rate movements into substantial losses. The "safe" nature of bonds becomes deceptive - leveraged bond positions can be wiped out by normal interest rate volatility.

Bond leverage also creates significant cash flow mismatches. While unleveraged bonds provide predictable income, leveraged positions require ongoing margin payments and face margin calls during adverse price movements. This transforms bonds from income-generating assets into potentially cash-consuming positions.

Stocks vs Bonds: CFD leverage comparison table

What are common beginner mistakes to avoid with Stock and Bond CFDs?

Some of the most common mistakes beginner traders make when trading stock or bond CFDs include:

Misunderstanding leverage

Ignoring overnight financial costs

Treating CFDs like investments

Poor risk management

Those mistakes can occur with both stock CFDs and bond CFDs, but some mistakes are specific to each type.

Bonds are usually seen as less risky than stocks, both because they offer a more predictable income stream than dividends would, and because bondholders are given priority over shareholders if you owned corporate bonds and that company went bust. Government bonds are even less risky than corporate bonds, particularly ones issued by governments with stable economies like the UK, US, Germany and Japan.

Rising interest rates have a clearer correlation with bond prices, but those interest rate hikes can affect equity prices as well.

Bond prices generally fall when interest rates rise, as existing bonds with lower yields become less attractive compared to newly issued bonds that are offering higher rates.

When it comes to stocks, rising interest rates can push borrowing costs up for companies that need to borrow money to fund their operations or growth, which can result in lower profits and a falling share price. But there are a few sectors that can benefit from rising rates, such as financial services, where banks and brokers might earn more when rates are higher.

When trading CFDs, these movements create opportunities in both directions - there’s the potential to profit from falling bond prices by going short, or from rising stock prices in rate-beneficiary sectors like financial services by going long. The key is understanding how rate changes affect different asset classes and positioning yourself accordingly.

Stock and bond CFDs are sometimes used by traders for portfolio hedging purposes. Here's how this typically works. Bond CFDs can help hedge against interest rate risk or provide portfolio diversification. For example, if you hold a large position in technology stocks in your main portfolio, you could short a tech sector CFD as a hedge. Similarly, if your portfolio is heavily weighted toward stocks, long positions in government bond CFDs could provide balance during market downturns.

*Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and can change or may differ in a jurisdiction other than the UK.

Disclaimer: CMC Markets is an execution-only service provider. The material (whether or not it states any opinions) is for general information purposes only, and does not take into account your personal circumstances or objectives. Nothing in this material is (or should be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by CMC Markets or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person. The material has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Although we are not specifically prevented from dealing before providing this material, we do not seek to take advantage of the material prior to its dissemination.