Above all, Dalio believes that cause and effect relationships exist almost everywhere, and that if you can figure them out, there’s money to be made. When investing in commodities like soybeans and corn, for example, Dalio would forecast demand by looking at how many cattle, chickens and hogs were being fed and how much grain they consumed, one of the “causes” in the cause and effect dyad. To estimate supply, he’d look at how much soybean and corn acreage was being planted and how rainfall affected their yields – another “cause”. Dalio would then reconcile these two causes to arrive at the “effect” – how grain prices were likely to move in the future – and use that to profitably trade soybeans and corn.

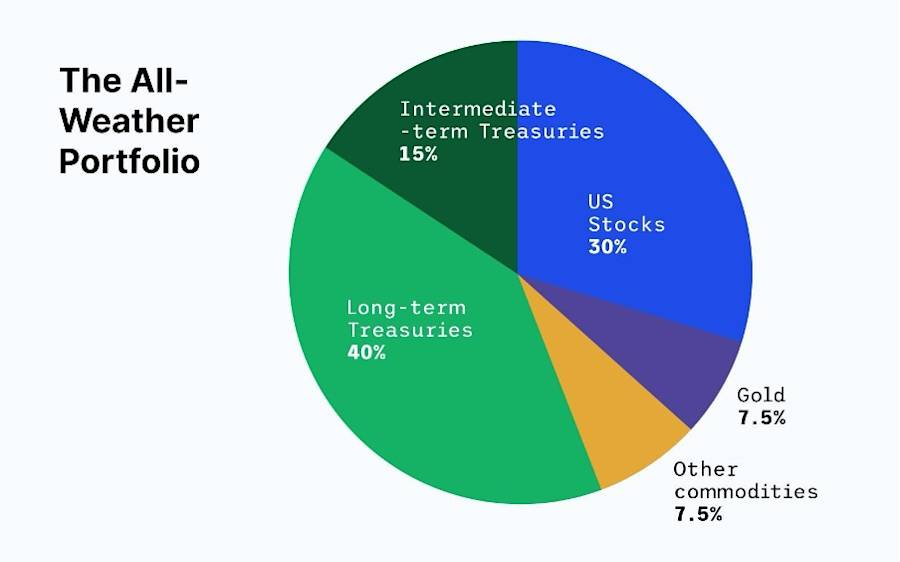

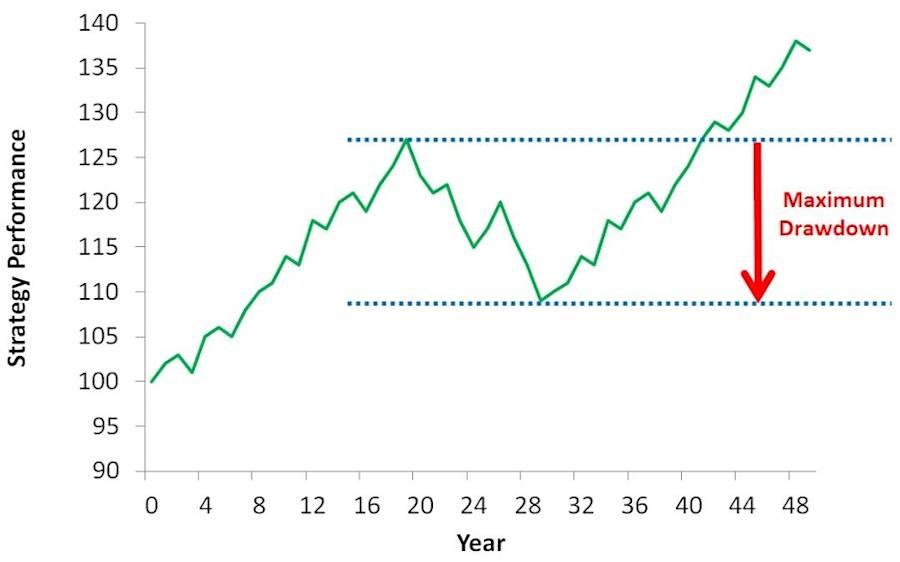

Another key principle is diversification, which Dalio views as the holy grail of investing. This is especially true when it comes to different asset classes – groups of similar assets such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and so on – that don’t move in the same way in a given economic environment. Specifically, Dalio believes 15 such “uncorrelated” investments can reduce a portfolio’s risk by 80% without sacrificing any significant return. Who said there’s no such thing as a free lunch?

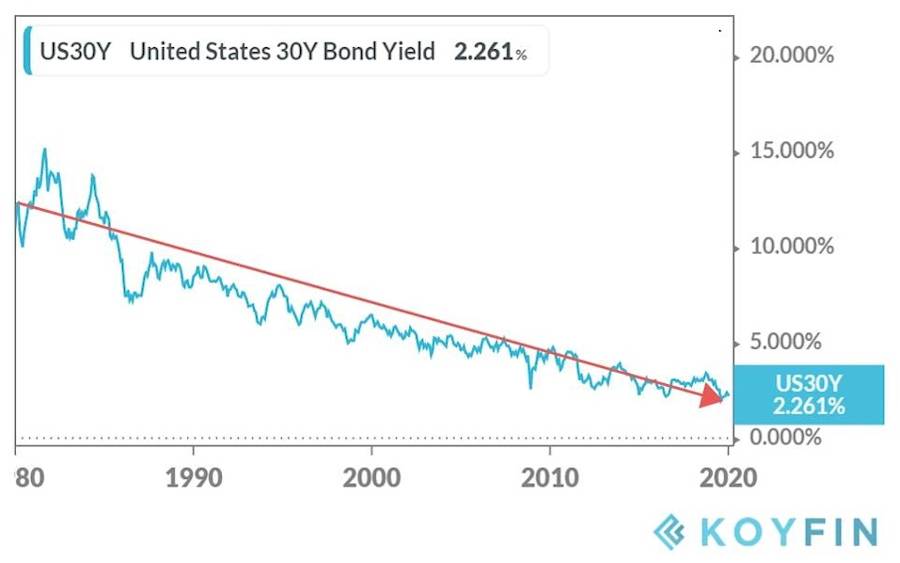

Dalio’s investing is also guided by the principle that economies and financial markets experience long-term cycles – and that it pays to understand these. Suffice to say that the economy undergoes protracted expansion (e.g. after the 2008 financial crisis), contraction (e.g. during the Great Depression), and long-term trends when it comes to inflation – the rate at which the prices of goods and services increase. These different environments have different impacts on different asset classes – and Dalio thinks riding those long-term waves beats constantly trying to time the market.

He’s also an advocate for being radically open-minded. That means trying to avoid having any biases – and to accept when you’re wrong. No one knows this better than Dalio: in the early 1980s, he lost almost everything betting that the economy was about to head south, even testifying in Congress and on TV to that effect. When meltdown failed to materialise, the resulting losses forced Dalio to dismiss all his employees as he could no longer afford to pay them…

While Ray Dalio has a whole host of other principles, the ones above are some of his most important ones when it comes to investing. In this Pack we’re going to show you how Dalio put these principles into practice, creating a portfolio meant to perform well in all economic environments – and walk through how you can construct something similar...

The takeaway: Ray Dalio is a successful investor who sticks to a series of investment principles, including cause and effect relationships, riding long-term trends, diversification, and being radically open-minded.

Ray Dalio’s strategic asset allocation & risk parity explained

Before we dive into a discussion of Ray Dalio’s famous All-Weather Portfolio, even seasoned investors may benefit from a reminder about strategic asset allocation – and how risk parity, a technique pioneered by Bridgewater Associates, aims to improve upon traditional versions of this.

Strategic asset allocation involves building a portfolio based on target allocations for different asset classes, and then rebalancing that portfolio regularly to make sure it stays that way. One well-known allocation is the “60/40 portfolio” – where an investor places 60% of their portfolio in stocks and 40% in bonds. A year later, stocks may have performed well but bonds declined – causing the portfolio’s value to skew 65% stocks and 35% bonds. Since that’s a deviation from their initial targets, the investor will then sell stocks and buy bonds to bring the whole portfolio back to a 60/40 split. So far, so simple. But how – and why – is such a mix determined in the first place?

The general idea is to have an allocation that provides a certain balance between risk and return over a long time horizon, tailored to the investor’s goals and therefore their risk tolerance. For example, a young individual saving for long-off retirement can afford to take on more risk – allocating a higher proportion to stocks because, while volatile in the short run, they also offer the highest long-term expected return. An individual very close to retirement, on the other hand, can’t afford to take on loads of risk – and so might lean more towards safer government bonds.

Dalio is a big proponent of strategic asset allocation: it fits in nicely with many of his investment principles. As well as supporting diversification, especially across different asset classes, strategic asset allocation is an investing strategy that tries to capture long-term market cycles. It also shuns bias. For example, some investors might avoid shares after a big stock market crash but in retrospect, that would probably have been the most opportune time to buy stocks. Strategic asset allocation, with its constant weighting to different asset classes, is an inherently open-minded strategy that makes sure you’re invested during both good times and bad – and that tends to pay off in the long run.

As Dalio himself puts it: "The most important thing you can have is an excellent strategic asset allocation mix. In other words, you're not going to win by trying to get what the next tip is – what's going to be good and what's going to be bad. You're definitely going to lose. So what the investor needs to do is have a balanced, structured portfolio – a portfolio that does well in different environments."

One of strategic asset allocation’s benefits, in other words, is that it’s diversified across different asset classes that tend not to move in lockstep – both reducing risk and allowing a portfolio to hold up well in different environments. Infrequent rebalancing, meanwhile, means less wasted money on trading fees and better tax treatment. Strategic asset allocation is designed as a hands-off approach that doesn’t require massive amounts of time and resources. As a buy-and-hold strategy, it reduces the human error of trying to time the market or letting emotions interfere with investment decisions. And best of all, the technique can be easily implemented using exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that track broad asset classes such as stocks, government bonds, corporate bonds, commodities, and so on.

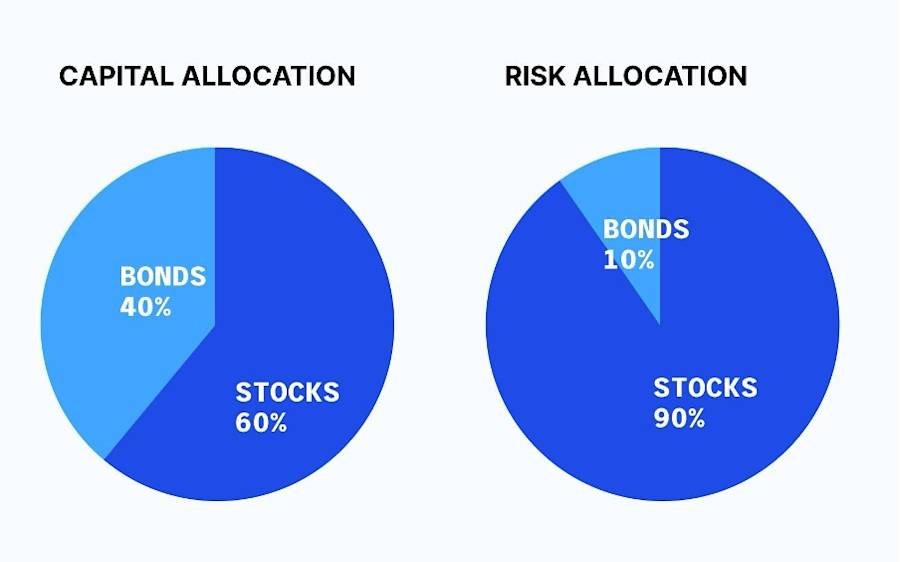

One of the main criticisms of strategic asset allocation, however, is that it’s too focused on arbitrary capital allocation rather than risk allocation. A typical 60/40 portfolio, for example, splits money between two types of investment that don’t tend to move in the same direction. But the problem is that stocks are a lot more volatile than bonds, and a 60/40 mix means the bulk of a portfolio’s risk is coming from stocks’ piece of the pie – as illustrated below.