Luxury yoga-inspired clothing company Lululemon Athletica [LULU] was a mess just 18 months ago. Back then analysts described it as “stretched-out spandex” and compared its stock – perhaps inevitably – to a “lemon”.

Retail was also supposed to be dead. Footfall in Lululemon’s various stores was low, the variation of activewear it pioneered seemingly “off trend”, with competitors such as Under Armour [UAA] and Nike [NKE] eating into what market share there was left of the athleisure industry (or luxury sportswear, where sportswear meets fashion; there are various definitions) that Lululemon had played a big part in creating.

In May 2017, Lululemon was at the $48 per share mark (down from a high of $82.50 in mid-2013). And yet the company has completed a rapid turnaround since then, culminating in profits nearly doubling in the quarter up to August, compared to the previous year.

The stock price has obligingly followed the increased profits, growing more than 220% from the 2017 low by September 2018. And although it has been hit by the recent market turmoil, many analysts remain bullish.

Either way, Lululemon is still valued at just under $20bn, making it nearly half the size of Adidas [ADS] – with analysts and fund managers describing it as “virtually perfect” and in “a league of its own”.

220% - Lululemon price gains May 2017-September 2018

It is a spectacular rise for a bricks-and-mortar retail company that was started in 1998 by a man selling women’s yoga leggings (which now cost as much as $118 a pair).

Leg up

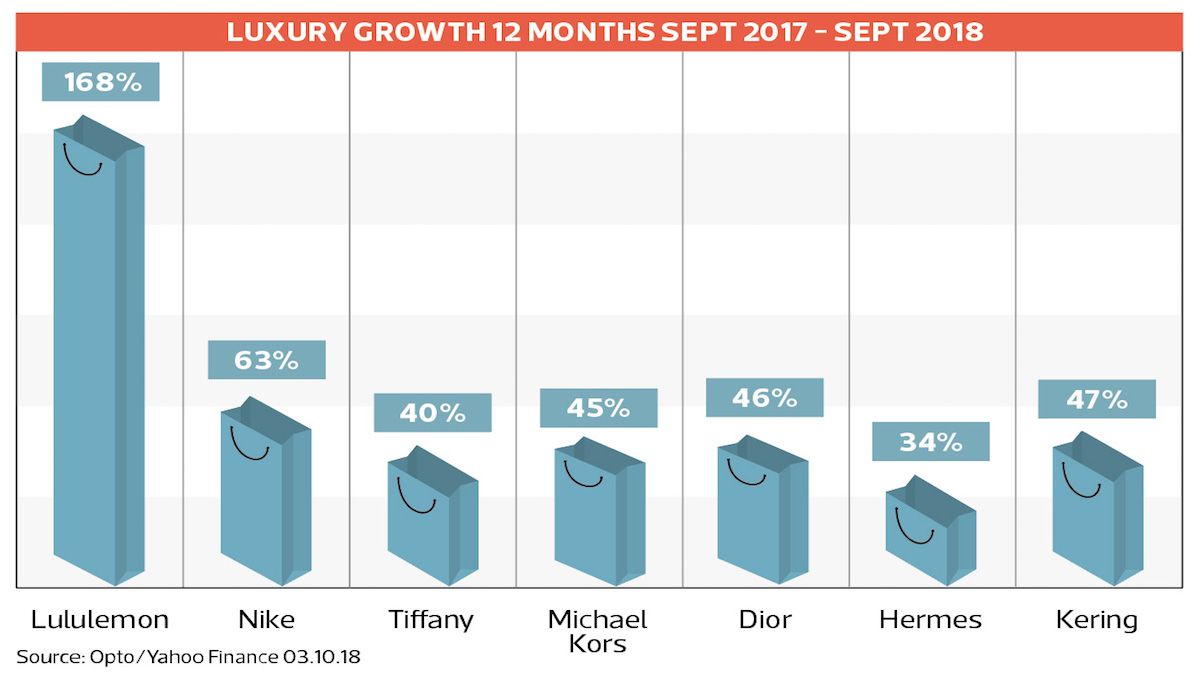

Lululemon’s rise is mirrored across the luxury and sportswear industry. Nike – partly in response to the threat of Lululemon’s success, partly due to changing tastes redefining luxury – has increasingly moved into the luxury arena with premium offerings and growing price tags.

In turn, it has seen its value spike. Nike, the third-largest clothing company in the world, hit an all-time high in 2018, gaining more than 60% over the 12 months to September.

Following a number of stagnant years across traditional luxury retail, Dior [CDI] and Michael Kors [KORS] have all posted far stronger growth figures than the S&P 500. Likewise, Tiffany [TIF], Hermès [RMS], LVMH (which owns Louis Vuitton) and Kering [KER] (which owns Gucci) have all hit unparalleled highs in 2018.

Richemont [CFR], owner of Cartier and the world’s third-largest luxury goods group after fierce rivals LVMH and Kering, is one of the few stocks to be down this year.

But part of the reason for the downturn is due to its high spending and investment: €200m went on buying back excess watch stock to prevent third-party retailers discounting its brands (€500m worth of excess stock has been destroyed in the past two years to preserve pricing).

$20.3bn - Market cap of Lululemon

Meanwhile, €2.7bn was used to purchase the remaining shares of luxury online retailer Yoox Net-a-Porter a move which is expected to facilitate the company pushing further into online retail, and help build out direct-to-consumer sales.

Despite Richemont’s stuttering performance, the fortunes of the luxury industry as a whole has completely transformed from the middle of the decade, when Lululemon was stagnant and the collective value of the 10 biggest luxury brands slumped by 6% in 2015 and 5% in 2016.

This year, the collective growth is 28% (it was 4% in 2017), according to the Top 100 Most Valuable Global Brands, a ranking and report by Kantar Millward Brown and WPP.

Perhaps the stock that most encapsulates luxury retail’s resurgence is Michael Kors. The company, which floated in 2012, reached its all-time high of nearly $100 a share in 2014 before crashing to just below $35 in July 2017. Sales had been consistently falling and the company announced it would close more than 100 stores.

It has since bounced back to about $70, gaining nearly 120% since its 2017 low. The retailer, famed for its handbags, acquired Jimmy Choo [CHOO] in August 2017 and, in the same month, it was reported that quarterly sales fell less than expected. By November, year-on-year sales were up and revenue targets were being exceeded as a new strategy began to take effect. It posted revenues of $1.2bn, a year-on-year increase of 26% in the most recent quarter.

28% - Growth of top 10 luxury brands in 2018

-6% - Decline in 2015

It has also reduced its range of products while becoming less reliant on handbags, with the Jimmy Choo acquisition providing an important boost, and seemingly catalysing the development of the company into a luxury conglomerate: in September the company announced the purchase of Versace, one of the most recognised and respected names in ultra-luxury.

As with the wider sector, China has been a key arena. “The company is beginning to see the benefits of its long-term growth strategy,” Josh Rudnik, a financial blogger at Seeking Alpha, commented in August following Michael Kors’ latest earning release, pointing out that the main driver of performance was China, as well as Japan and Korea.

So why the surge across the sector?

Between 2014 and 2016, the decline in value of luxury brands coincided with a slowdown in consumer purchasing in China. This picked back up in 2017, with companies like Lululemon and Tiffany massively benefiting.

The country now makes up a third of all luxury retail purchases globally – and consumers are buying online, as well as in malls, with the country’s two biggest online retailers launching luxury offerings in 2017, and international sellers like Farfetch (see part 2), also investing heavily.

It’s easy to see why: the average luxury-buying household in China spends double that of the average French or Italian household making luxury purchases, according to research by McKinsey.

The growth in spending looks set to continue. The consultancy believes that there will be 7.6 million households in China buying luxury goods by 2025, “double that of 2016, and equivalent to the size in 2016 of the French, Italian, Japanese, UK and US markets combined”.

However, its report was published in 2017 – before President Donald Trump launched his trade war. There are now concerns that, if ongoing trade tensions that have already hurt China’s economy spread to its consumers, sales will slow down. There’s also a chance that US luxury companies such as Lululemon and Michael Kors could eventually find tariffs added to their products, which could also help the Chinese counterfeit industry.

While trade friction threatens to harm American luxury brands, another Trump policy may have had the opposite effect. Huge tax breaks for corporations and the wealthy has helped luxury’s margins in the US. Companies have had their profits boosted by lower tax obligations and, with wealthy individuals paying less tax, there’s more money available to spend on high-end items.

Millennials have been an important part of the surge in spending in China, and an emerging luxury habit from this age group in the US and Europe has provided retailers with a new group of consumers. Brands have been quick to spot this, clearly courting them by moving into casual and sportswear-inspired styles that fit millennial tastes, and investing heavily in e-commerce.

“In the US, millennials are getting to wealth faster and they’re much more ethnically diverse,” says Beth Howard, a director at Kantar Millward Brown. “They often buy into the experience around the product. The classic brands are responding in many ways, certainly by perfecting their e-commerce presence.”

It’s a strategy Lululemon seems to have perfected. William Blair, a Chicago-based fund-management firm, told investors in August this year: “Lululemon has an enviable competitive position with a powerful combination of highly productive stores, aspirational proprietary product, a healthy e-commerce channel and the potential to ultimately nearly triple revenue as the concept continues to expand across the globe.”

“US millennials are getting to wealth faster, and often buy into the experience around a product.” – Beth Howard, Kantar Millward Brown director

On the run?

It’s meant Lululemon has been able to not only stay relevant, but grow. During the company’s downturn years, much was made of increasing competition from both new companies, like Under Armour, and existing behemoths, such as Adidas and Nike, moving into the luxury active wear industry.

A 2015 article on the news website Quartz concluded that “now that the athleisure trend has blown up, Lululemon faces competition from every which way”. The creation of the trend that had driven its growth was “now bringing it down”.

Under Armour was going from strength to strength with a proposition that appealed to men as well as women. It was consistently cited as the brand that would destroy Lulu. After floating in 2015, it reached $104 a share. It’s now at the $19 mark; and that’s only following a recent rally that analysts are split on whether it will be able to sustain.

Part of Under Armour’s failure was down to its focus on the technical aspects of its clothing rather than the lifestyle element. However, Lululemon didn’t make the same mistake: the brand maintained its connection to its audience through meet-ups and yoga classes in bricks-and-mortar stores, riding the wave of the ever-growing interest in wellness and working out – and looking good while doing it.

Lululemon also learned from its mistakes. Over-production was cited by analysts as a barrier to growth, leading to the company’s stores offering large discounts on stock, and bringing down its exclusivity and value as a luxury item.

After finding that the number of clearance rails at Lululemon’s stores had almost doubled in 2014, analyst Susan Anderson said: “Given increasing competition in women activewear and a competitive men’s market, we think that Lulu may not be able to claw back margin with higher selling prices on product.”

But that’s old news. Today, a lack of discount is something that is being praised by analysts as a key factor in profit increases and future growth. “Lululemon’s price integrity is another reason for its outperformance,” GlobalData Retail’s Neil Saunders wrote in a note to investors in August. “Promotional periods notwithstanding, products are not discounted and customers know they must pay the full price if they want the product.”

Part of the club

One of the biggest buzzwords in luxury retail is “experience”. It might be hugely overused, but retailers, analysts and marketeers are convinced it’s what millennials and the surrounding generations have come to expect from luxury.

“They earn in order to experience,” explains Veronika Vdacna, global business director at Mindshare. “Although some of these ‘new rich’ are millennials, there are also other generations that share similar values.”

Offering activities such as yoga, running or spin classes naturally gives Lululemon this advantage. The company is able to emphasise its experiential element because it is essentially a direct-to-consumer brand.

Unlike Nike or Under Armour, it is not stocked by third-party retailers and department stores - other than in concessions and selected yoga studios and gyms - giving the brand a much closer touchpoint with customers.

During the years that Lululemon’s margins were dropping, it was in part due to investments in international expansion, particularly in China and the rest of Asia. It’s an investment that has paid off: as Chinese spending in luxury has increased, Lululemon has been able to take a sizeable slice of the pie.

Its e-commerce business in China grew by 200% in the second quarter of 2018, compared to the same period in the previous year. At a time of the rapid rise of millennial-focused online direct-to-consumer brands such as glasses retailer Warby Parker – which have been forced to move into bricks-and-mortar retail – the 20-year-old Lululemon is the original brand in the crop.

Its continued success through its 415 stores and investment in e-commerce has paid major dividends: online sales grew by almost 50% in the second quarter of 2018, compared to the same quarter in 2017. And as the well-being and experience trend isn’t showing any signs of slowing down, Lululemon’s fortunes are expected to soar. So who’s a lemon now?

Disclaimer Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

CMC Markets is an execution-only service provider. The material (whether or not it states any opinions) is for general information purposes only, and does not take into account your personal circumstances or objectives. Nothing in this material is (or should be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by CMC Markets or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

The material has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Although we are not specifically prevented from dealing before providing this material, we do not seek to take advantage of the material prior to its dissemination.

CMC Markets does not endorse or offer opinion on the trading strategies used by the author. Their trading strategies do not guarantee any return and CMC Markets shall not be held responsible for any loss that you may incur, either directly or indirectly, arising from any investment based on any information contained herein.

*Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and can change or may differ in a jurisdiction other than the UK.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy