Research shows that founder-led companies tend to outperform their counterparts in a range of areas, including innovation and long-term share price performance.

Understanding the long-term goals of these founders is key for investors seeking to grasp their companies’ full value.

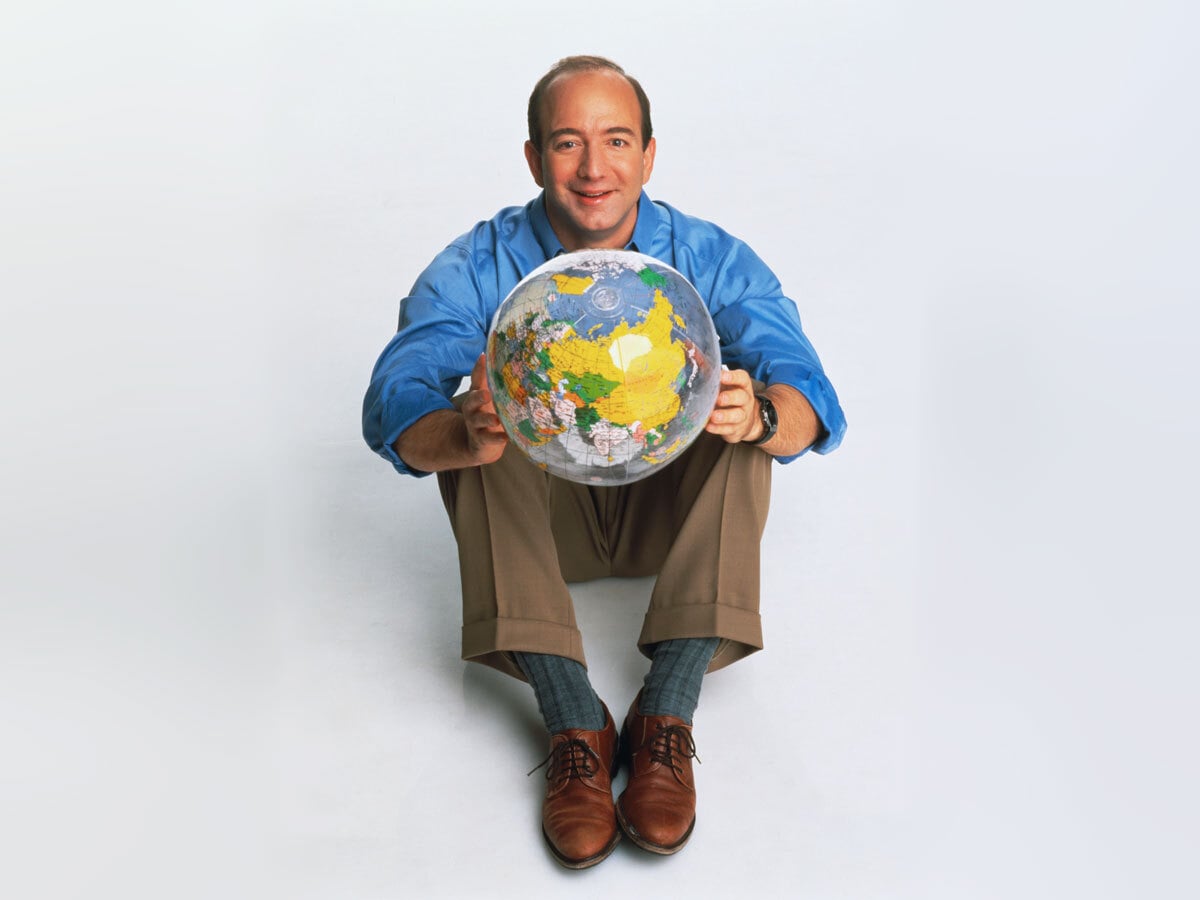

Jeff Bezos built arguably one of the most significant companies in the history of commerce. Through his pursuit of superior customer experience and a realisation that the internet could be the perfect medium to sell any kind of good imaginable, Amazon.com has grown to become one of the world’s most valuable businesses.

This is Day 1 for the Internet and, if we execute well, for Amazon.com. Today, online commerce saves customers money and precious time. Tomorrow, through personalization, online commerce will accelerate the very process of discovery. Amazon.com uses the Internet to create real value for its customers and, by doing so, hopes to create an enduring franchise, even in established and large markets. — Jeff Bezos’ original letter to Amazon shareholders, 1997

No Regrets: What Makes Jeff Bezos Different? The picture of the future painted by Bezos in his first-ever letter to Amazon [AMZN] shareholders (which he attached to every subsequent annual letter) rings truer in hindsight than anyone could have foreseen at the time. Through his vision, Jeff Bezos has fundamentally changed the way that goods and information are distributed. The original letter is groundbreaking in several respects. It lays bare the rationale that underpinned the company’s early decision-making: a focus on the long term, a relentless focus on customers, and a commitment to transparency that the letter itself embodied. These were radical ideas in 1997, but they are now almost ubiquitous among successful businesses. Bezos was born in 1964 in the US state of New Mexico, and after studying computer science and electrical engineering at Princeton University took a job at Fitel, a telecommunications company whose goal was to create a communications network for traders. After two years there and a further two at Banker’s Trust (now part of Deutsche Bank [DB]), Bezos joined Wall Street hedge fund DE Shaw. He became the firm’s youngest-ever Senior Vice-President. It was during his time here that he realised the enormous potential of the internet. His decision to leave D.E. Shaw is generally attributed to one of Bezos’ most enduring cultural legacies: the regret minimisation framework. In The Everything Store, the biography of Bezos written by Brad Stone, Bezos says: “I knew when I was eighty that I would never, for example, think about why I walked away from my 1994 Wall Street bonus right in the middle of the year at the worst possible time. That kind of thing just isn’t something you worry about when you’re eighty years old.” |

Something They Could Not Get Any Other Way

“We set out to offer customers something they simply could not get any other way, and began serving them with books. We brought them much more selection than was possible in a physical store (our store would now occupy 6 football fields), and presented it in a useful, easy-to-search, and easy-to-browse format in a store open 365 days a year, 24 hours a day.” — Jeff Bezos, Amazon 1997 shareholder letter

In 1455, Johannes Gutenberg began printing copies of the Bible on his newly invented printing press, paving the way for books to become the first mass-produced products in the world.

Some 540 years later, books were once again the proving ground for a new generation of commerce and distribution. According to Business Insider, when setting up his business Amazon.com, Bezos chose books as they were the most feasible and promising product.

Having characterised the internet of the early–mid-1990s as “the World Wide Wait” in Amazon’s first shareholder letter, Bezos recognised that it, in fact, held the potential to greatly improve the experience of consumers shopping for goods.

The Plan: The Everything Store

“There are more items in the book category than there are items in any other category.” — Jeff Bezos, 2018

Bezos knew that the abundance of books in circulation made them the product to build out his vision of an internet store that categorised its products meticulously.

With categorisation came personalisation. Amazon was, according to e-commerce training company Econsultancy, the first company to deploy personalisation at scale. By 2015, Amazon’s personalised recommendations were already estimated to add 10–30% to its revenue, by making it easier for customers to discover and purchase products that matched their interests.

This made Amazon a phenomenal bookstore, and as the company grew, two strands of Bezos’ plan materialised.

The first of these was to become an “everything store”. Over time, it began adding more products (such as, in the early years, CDs and electronic goods). Amazon can now deliver a bewildering range of products, from groceries to prescription drugs.

The second strand — Bezos’ commitment to customer experience — underpinned and enabled this product diversification. This commitment didn’t end at the store checkout but encapsulated the entire consumer funnel from store to door via innovations like next- or same-day delivery.

This, in turn, has led to Amazon breaking yet more ground: that of the automated warehouse. Bezos’ emphasis on customer service made Amazon a key innovator in the field of warehouse automation as its operations scaled, and it remains at the forefront of research into robotics technology.

Many of Amazon’s biggest innovations are rooted in Bezos’ rigorous approach to customer experience.

Its logistics arm, Amazon Logistics, was launched in 2015, two years after United Parcel Service [UPS] failed to deliver a number of Amazon parcels in time for Christmas, prompting the firm to take logistics in-house.

Similarly, the unit that has perhaps had the greatest imprint on the present and future of the internet, Amazon Web Services (AWS), began life as a tool to help power Amazon’s website and its third-party sellers.

Soon after its inception, Bezos realised that the company could generate revenue by selling cloud-hosting services to third parties. Now, AWS is the world’s largest cloud service provider, with 32% of the total market share as of the second quarter of 2023, and accounted for 62.5% of Amazon’s operating income in its most recent results.

Progress: From Vision to Reality

Bezos stepped down as CEO of Amazon in 2021, though he is still the company’s executive chairman. During his 27 years at the helm, Bezos grew Amazon from nothing to a $1.6trn business and was himself the world’s richest person. At the time of writing, Amazon is the fifth-largest company in the world by market capitalisation.

Amazon has been a constant innovator throughout that time. As well as cloud computing, its products have helped pioneer products such as e-book readers, voice-activated assistants, cashless shopping and video streaming.

Moreover, Amazon has had a transformational impact on commerce. Bezos’ vision of a world of online shopping where personalisation, categorisation and automation create a seamless customer experience has become a reality.

Few would dispute, today, that Bezos’ vision has been achieved.

Investment Takeaway

Amazon’s stock has gained 81.1% in the year to 21 December. Over the past five years, the stock gained 120.9%, and since its IPO in 1997 the stock has gained 745%.

Because it has achieved the goal of being “the everything store”, Amazon is also a substantial holding in a wide range of thematic ETFs. As of 21 December, it is the top holding in the ProShares Online Retail ETF [ONLN]; the MUSQ Global Music Industry ETF [MUSQ]; the Vanguard Consumer Discretionary ETF [VCR]; and many others.

ONLN and VCR have gained 26.1% and 39.4% year-to-date respectively, while MUSQ has fallen 1.4% since launching in July.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy