Research shows that founder-led companies tend to outperform their counterparts in a range of areas, including innovation and long-term share price performance.

Understanding the long-term goals of these founders is key for investors seeking to grasp their companies' full value.

Elon Musk, for example, has been involved in many seemingly disparate ventures. However, more than stand-alone enterprises, they must be seen as components of his over-arching project: to enable a significant human population to live on Mars.

What Makes Musk Different?

Elon Musk was the world’s richest person at the time of writing, $45.6bn clear of second place. His success is no doubt partly attributable to his voracious appetite for knowledge — as a child, Musk would read science fiction and non-fiction for 10 hours every day — as well as his unique perspective on the world.

Musk, like many founders, approaches business as an exercise in problem-solving, and his favourite problems are the existential challenges facing the human race.

“For me, it was never about money, but solving problems for the future of humanity.” Elon Musk, 2012

It is this desire to solve humanity’s big problems that led Musk to invest heavily in space travel as part of his ultimate vision: creating a sustainable human population on Mars.

“We don’t want to be one of those single-planet species. We want to be a multi-planet species.” Elon Musk, 2021

The Vision: Beyond the Horizon

Musk’s vision for humanity begins with the Fermi paradox, which asks why Earth has not been visited by aliens. Given the antiquity of the universe and the relative youth of our solar system, if interstellar travel is hypothetically possible, then intelligent life should, by now, have reached Earth.

Musk thinks that civilisations go through a filtering event that does away with them before they develop the technology required to travel through space. He wants humanity to outlive this threshold: “If civilisation is tenuous, then we must do whatever we can to ensure that our already-weak probability of surviving is improved dramatically,” Musk told the Wait But Why blog in 2015.

Climate change is one candidate for the hypothesised Great Filter.

Buying Time

Elon Musk’s plan revolves around buying humankind as much time as possible to make the journey to another planet. Climate change is the ticking time bomb, the clock against which humanity is racing.

“Changing the chemical composition of the atmosphere and oceans by adding enormous amounts of CO2 is the dumbest experiment in human history.” Elon Musk, 2015

As the clock races, the spotlight turns to Tesla [TSLA]. The US Environmental Protection Agency says that transport is the single-largest source of global greenhouse gas emissions. In 2003, Musk — who has a long-standing interest in clean energy technology — found himself in a position to invest in a small electric vehicle (EV) start-up called Tesla Motors.

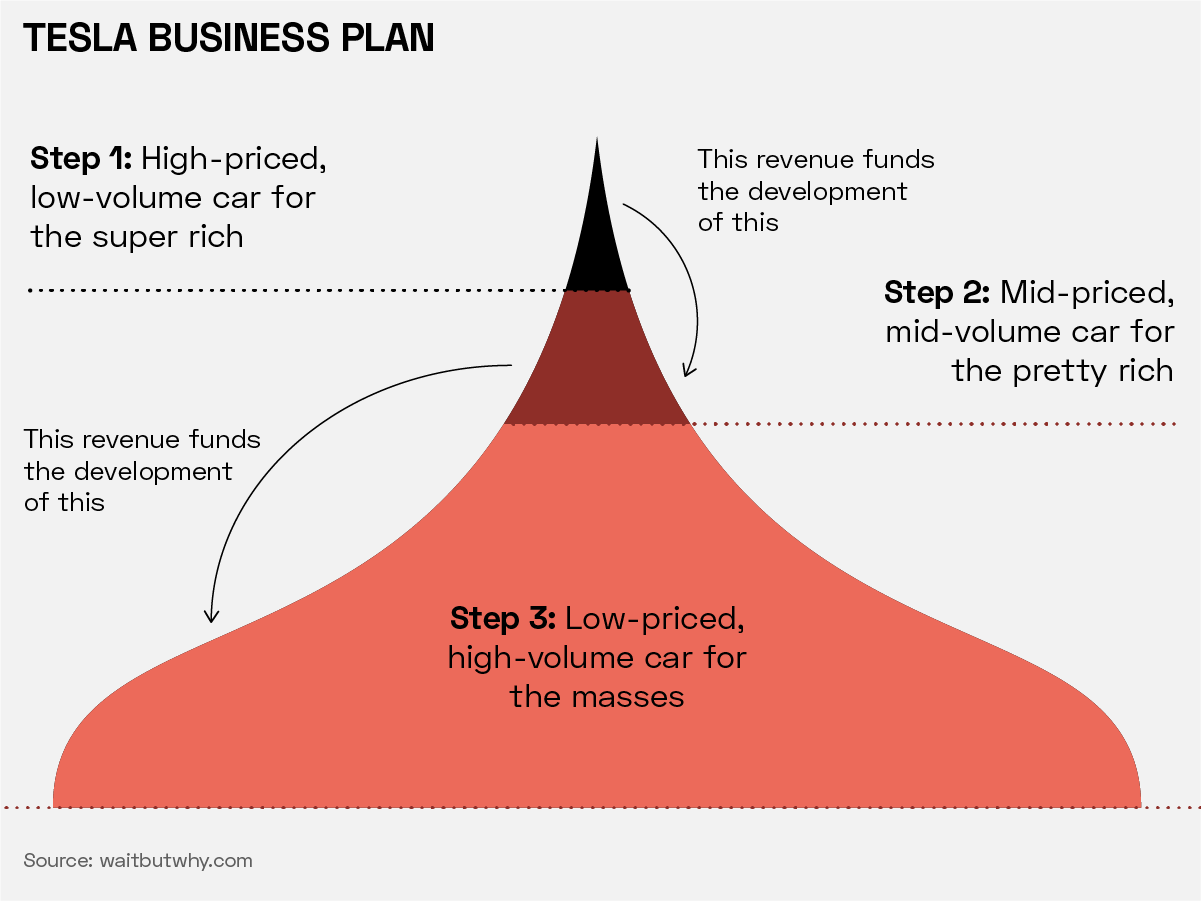

The company planned to disrupt the entrenched internal combustion engine car industry. First, they would manufacture low-volume, high-price EVs for super-rich customers. Then, they would produce a high-end car for a slightly larger, slightly lower-income market. And thus, the company would work its way towards the mass production of EVs.

Musk eventually took over as CEO of Tesla in 2008. Fifteen years later, it is now the ninth-largest company in the world by market cap.

Planet B

When he first encountered Tesla, Musk was already CEO of SpaceX.

Regardless of whether climate change will eventually end human civilisation, there are numerous other candidates for the Great Filter. Any number of galactic events, from a supernova to a gamma-ray burst, have the potential to end human civilisation on Earth. Over a long enough time period, one is certain to.

Musk, therefore, views humanity’s stay on Earth as inherently finite. For this reason, he is actively working towards a concept known as planetary redundancy (or, as he calls it, life insurance for the species): a self-sustaining extra-terrestrial population of humans.

He estimates that to be truly self-sustaining, this population would need to comprise at least 1 million people. The obvious candidate is Mars, given its proximity to Earth and relatively human-friendly conditions compared to the other planets in the solar system.

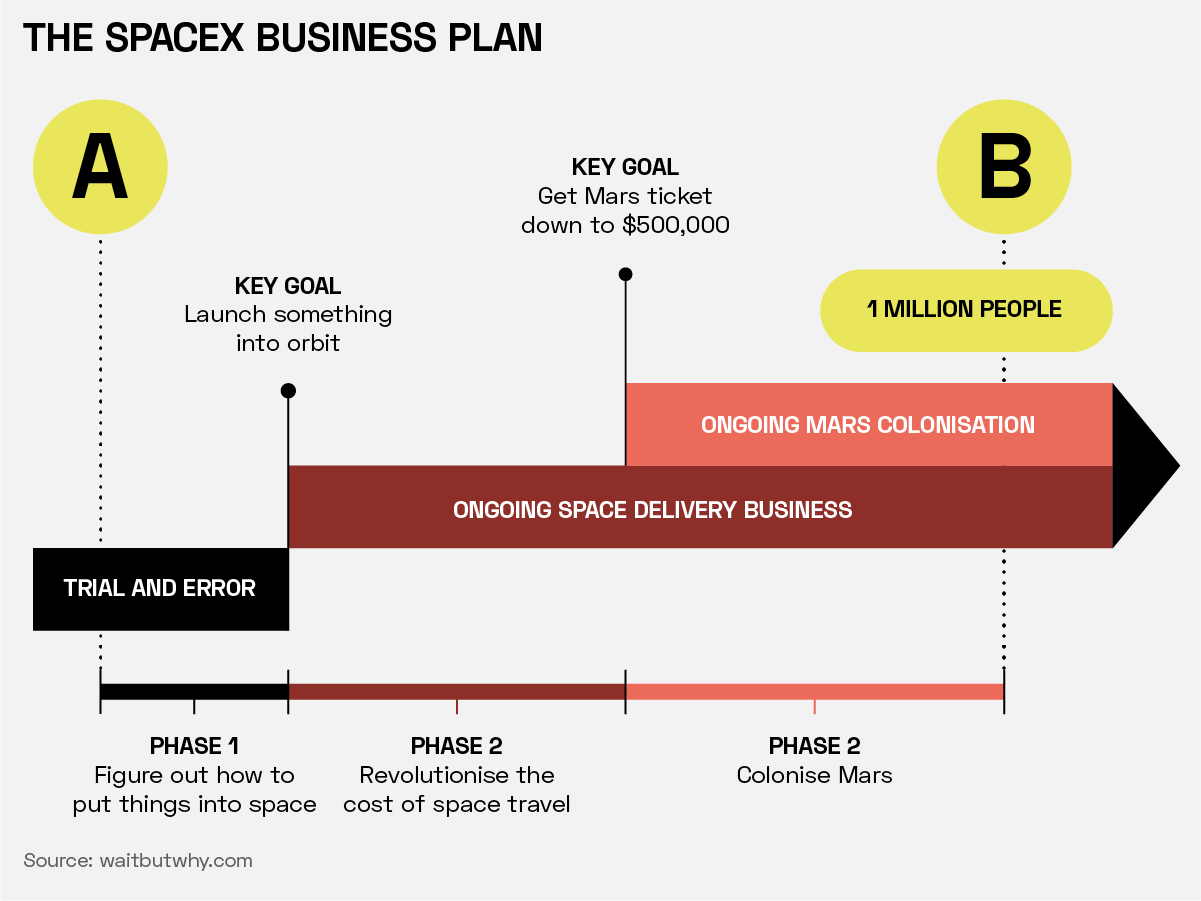

As with EVs, Musk views affordability as the key to effecting the revolution. While National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) budget cuts since the 1970s mean the agency no longer funds Mars colonisation projects, Musk believes that if the cost of reaching Mars fell to a level that 1 million people could afford, they would fund it themselves.

To that end, Musk plans for SpaceX to develop its own interplanetary travel technology from scratch. The research and development phase will be financed by charging fees to take cargo and humans short distances into space.

Like his hypothesised colonists, Musk had to self-fund SpaceX’s first four rocket launches, doing so with funds he made from the sale of PayPal [PYPL].

The first three launches failed, and with Musk’s available funds covering only four, the company’s existence was in danger. However, after a successful launch in September 2008, SpaceX was hired by NASA on a $1.6bn contract to make 12 deliveries to the International Space Station (ISS).

Giant Leaps and Bounds

At the time, SpaceX was the second privately funded organisation in history to launch something into orbit successfully. Today, a plethora of space companies jostle for control of the stratosphere, including two high-profile space tourism competitors: Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin and Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic [SPCE].

SpaceX has diversified, too. In addition to cargo, it now transports humans into space, including to the ISS for NASA. It also operates Starlink, which has around 4,500 satellites that power broadband connectivity across the world. On 31 October, the US Federal Aviation Authority concluded a safety review of the Starship rocket, bringing the craft — which SpaceX says is “designed to carry both crew and cargo to Earth orbit, the Moon, Mars and beyond” — one step closer to receiving a launch licence.

The greatest technical challenge involved in colonising Mars in the short term is getting there, and it is this problem that SpaceX is trying to solve. However, once there, other challenges will include making the planet — which currently has no atmosphere, liquid surface water or oxygen — habitable for humans, as well as the plants and animals that a population would need to cultivate.

Musk discussed some of these challenges in an interview with Popular Mechanics in 2019. He outlined his vision for the food supply to be based on plants grown in solar-powered hydroponic laboratories. It is noteworthy that Tesla has a solar energy business, which originated as SolarCity, a company that Musk’s cousins founded and which he purchased in 2016.

Elsewhere, Musk has hinted that another of his ventures, The Boring Company, could also have applications for a Martian colony. In 2017, Musk told the ISS Research and Development Conference that “getting good at digging tunnels could be really helpful for Mars”. Specifically, mining materials, including ice and creating underground, radiation-shielded habitats could be vital pieces of the Martian puzzle.

Will It Be Long?

Musk’s goal of colonising Mars consists of several stages. The first of these will involve an unmanned trip to Mars so SpaceX can check if it has the technical capability to get a rocket there and back again. Following that, further unmanned missions will deliver the equipment and resources that humans would need to create habitable conditions on Mars, such as water, oxygenation tools and fertiliser for crops.

Having previously suggested that the first of these trips could happen in 2020, Musk is yet to launch a mission to Mars. In October, he told the International Astronautical Congress in Azerbaijan that an unmanned test landing could be “sort of feasible within the next four years”.

He added that a manned mission to the Moon could use a Starship craft with only minor modifications from the version designed to reach Mars. That lunar mission is currently scheduled for 2025.

Musk told the Wait But Why blog in 2015 that he envisages a thriving city on Mars by 2040 but that he does not expect to reach 1 million colonists within his lifetime, anticipating that it will take 40-50 years of fleet migrations once the basic infrastructure is in place.

Investing in Musk’s Mars

Investors who want to tap into Musk’s visionary leadership are, at present, limited to Tesla, as SpaceX, The Boring Company and X are all privately held companies. Tesla shares fell 4.1% in the 12 months to 2 November.

There have been rumours in the past that Starlink might be spun off and made public. However, when asked about this in June, Musk replied that it would not be legal for him to speculate.

Various ETFs do, however, offer exposure to the space exploration theme, such as the ARK Space Exploration & Innovation ETF [ARKX], which fell 0.7% in the 12 months to 2 November.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy