Rare earth minerals are fundamental to the energy transition, but supply is dominated by China, and is becoming increasingly politicised in geostrategic trade wars. McKinsey views traders as an important source of liquidity for the sector, while other countries and regions could emerge as production hubs.

- Supplies of energy transition-critical rare earth minerals are tight, and heavily dominated by China.

- Geopolitical tensions are exacerbated by the potential for supply shocks.

- Could Africa be a relatively untapped source as companies seek to diversify their supply chains?

‘Critical minerals’ such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and rare earths are essential to the energy transition, but their supply chains are fraught with complex geopolitical considerations.

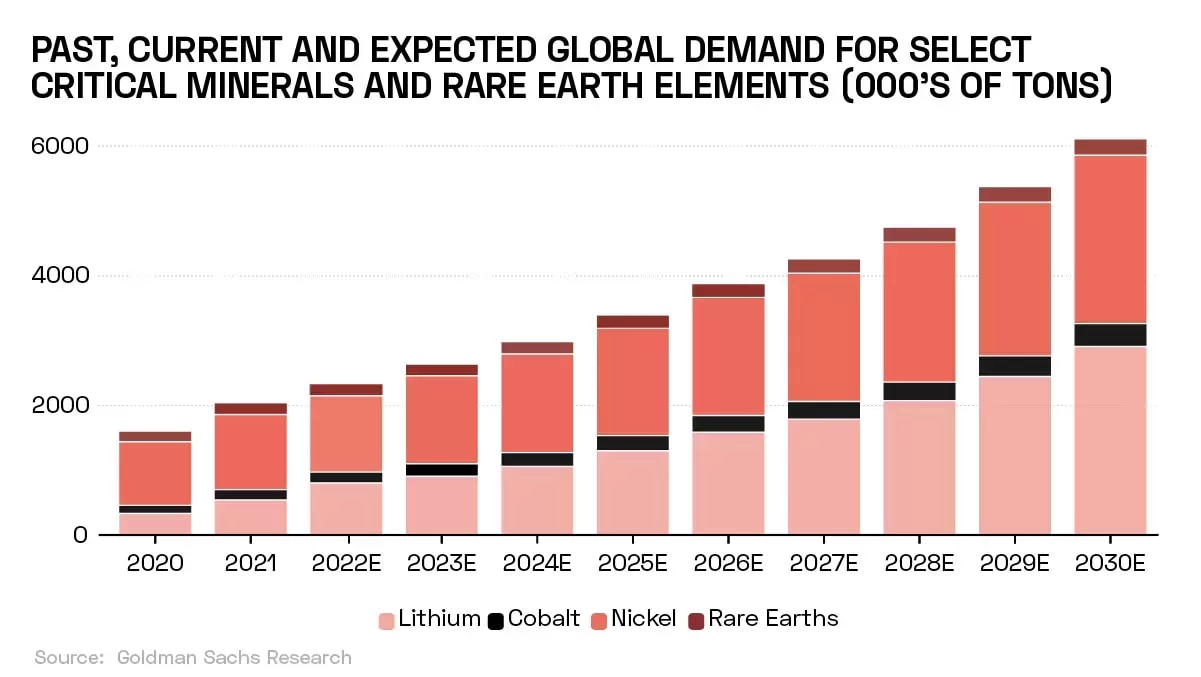

According to ‘Resource Realism: The Geopolitics of Critical Mineral Supply Chains’, a September report from Goldman Sachs Research, the market for critical minerals has doubled in size to $320bn over the last five years, and is expected to double again by 2030.

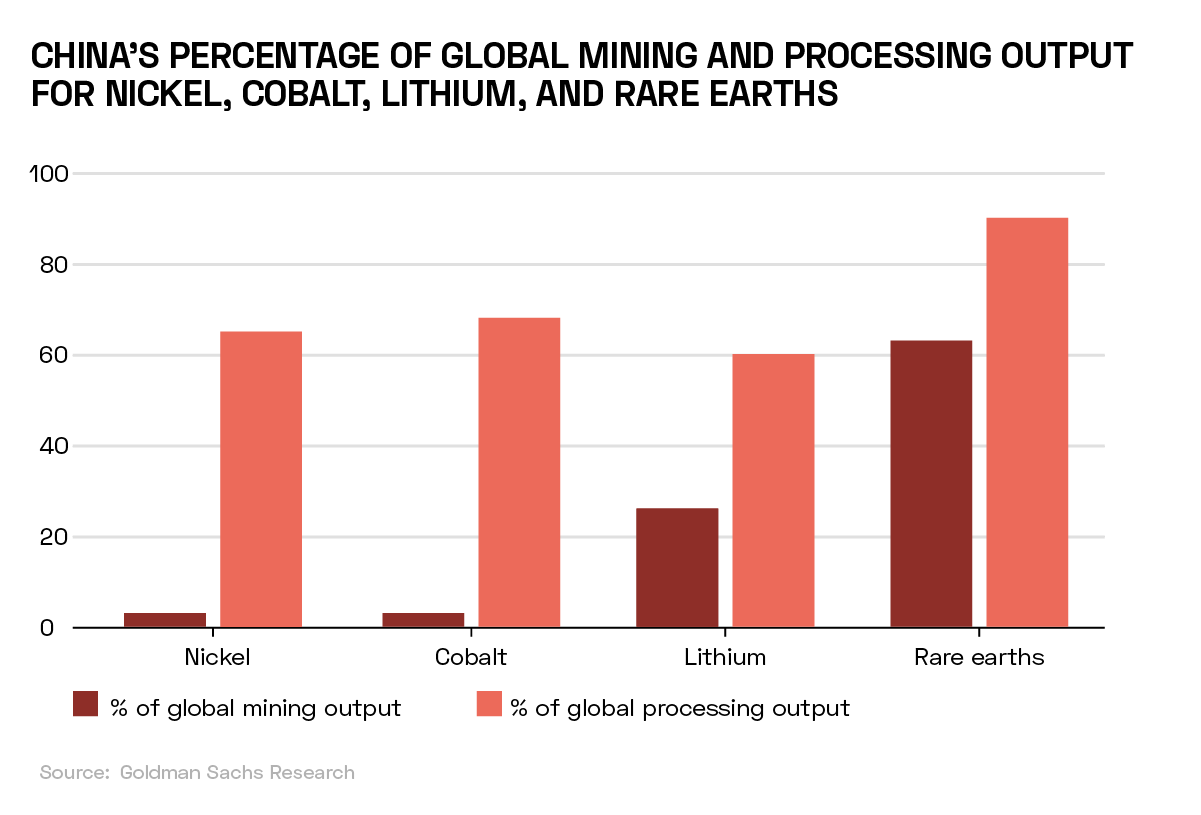

According to the report, “While there are reserves of different quantities of these essential materials all over the world, their supply chain is increasingly vulnerable to geopolitical shocks, as they are processed into usable, constituent materials predominantly — and for some almost exclusively — in one country: China.”

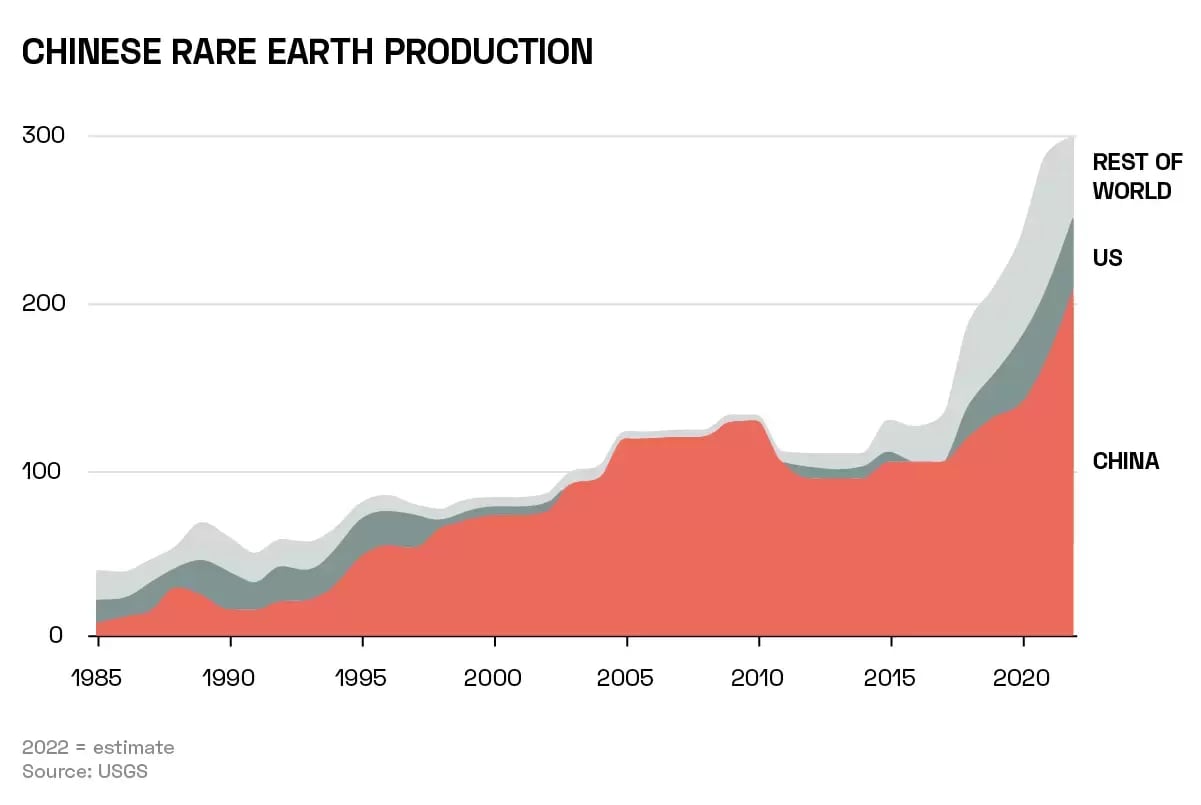

The situation is particularly stark in rare earth elements. China accounts for 85–90% of global mine-to-refining.

The decarbonisation goals of countries like the US and India are, therefore, heavily dependent on Chinese policy. US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said in April that “clean-energy supply chains are at risk of being weaponized in the same way as oil in the 1970s, or natural gas in Europe in 2022”.

In 2023 alone, China has blocked exports of graphite to Sweden, and implemented controls on exports of gallium and germanium to the US, in response to curbs on shipments of US-made semiconductors to China.

The Liquidity Trade

Strategy consultancy McKinsey believes that the global critical minerals shortage presents a trading opportunity. According to McKinsey, reaching net-zero global emissions by 2050 will require a doubling of the global resource base to maintain economic growth, and could entail up to $200trn investment in electric vehicles (EVs), upgraded power grids and low-carbon power.

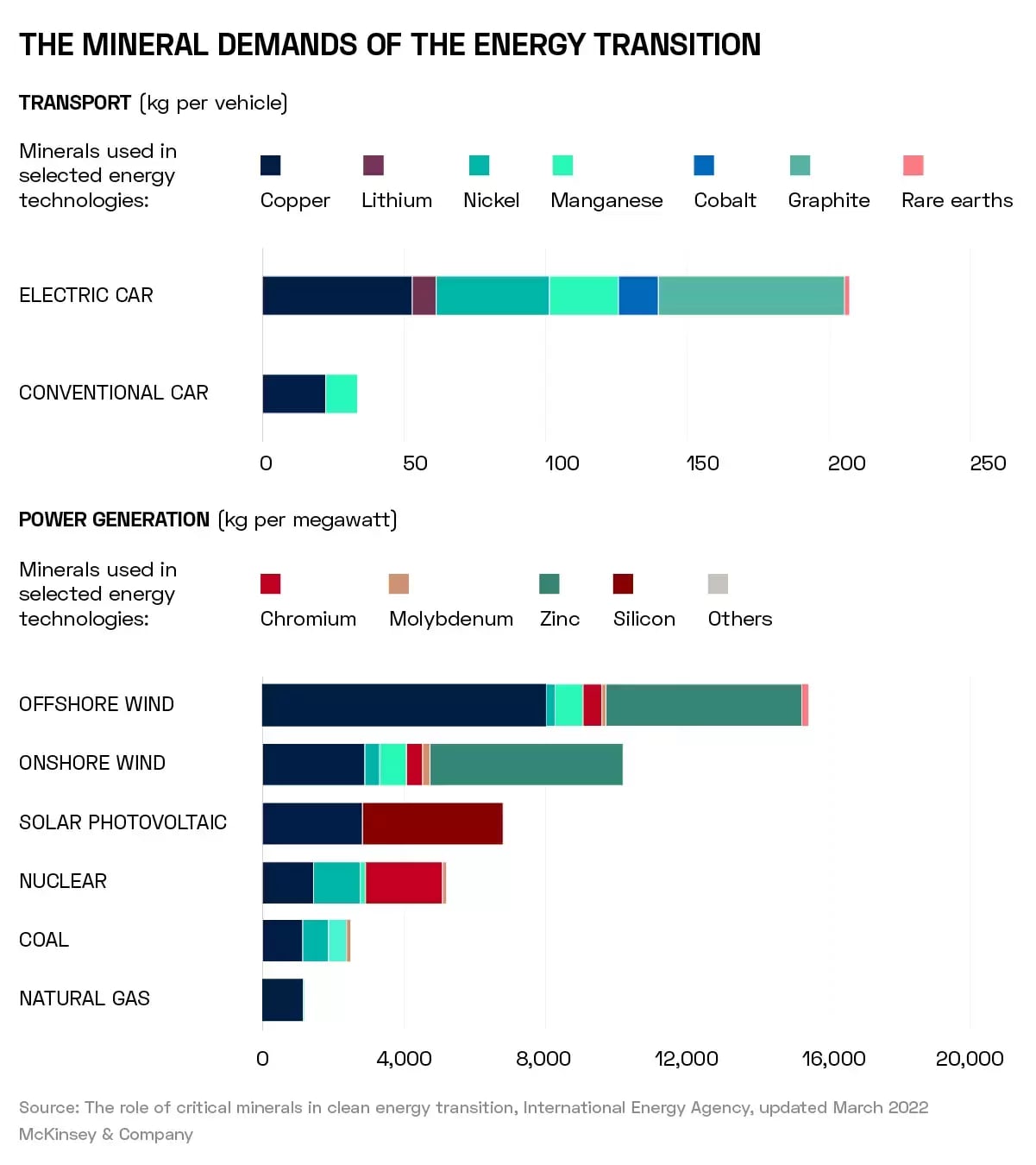

This is largely because technologies essential to the energy transition — renewable wind turbines and EV batteries — require more critical minerals than their fossil fuel-dependent counterparts. For example, a single offshore wind turbine needs 15 times more minerals to produce the same amount of power as a natural gas installation, while

EVs and their battery and charging infrastructure are expected to account for 50% of rare earth elements, 55% of cobalt and 36% of nickel in the year 2030.

The geopolitical angle also plays a central part in McKinsey’s analysis. In a September report titled ‘The Trading Opportunity that Could Create Resilience in Materials’, the consultancy discusses emerging “geostrategic bottlenecks”, such as Chile’s nationalisation of lithium production or Indonesia’s limits on nickel exports.

“Over the long term, countries could seek to use their mineral and metal production to gain a geopolitical advantage and build local industry and employment, a trend that could contribute to more regionalisation.”

Given the difficulties in increasing supply volumes for many of these minerals, McKinsey anticipates long-term deficits in certain key commodities. Commodity and energy producers still have incentives to prioritise short-term liquidity over capital expenditures and investments; that choice has exacerbated these deficits, and there are signs this trend may continue.

McKinsey says traders have both an opportunity and an important role to play in the solving of this supply imbalance, by providing liquidity to energy and commodity companies as they look to invest in increased output capacity, or innovations that circumvent constrained resources over the long term. This capital can also be drawn on to assist newer commodity players with risk management.

Chinese Monopoly

Establishing supply chains of rare earths that are independent from China will not be straightforward. The country dwarfs the rest of the world’s production of rare earth oxides, according to the Financial Times, and has a dominant position in the refining industry too.

The Financial Times notes that EU officials are concerned China could retaliate against Western protectionist measures, such as a recent Brussels probe into Chinese EV subsidies, by placing trade controls on the strategically critical rare earth minerals of which it is the world’s main supplier. Europe’s relatively high environmental and labour standards, as well as its lack of demonstrated rare earth deposits, may preclude it from establishing a supply chain that doesn’t involve China.

The geographic concentration of rare-earth supplies also means the market is particularly vulnerable to political shocks. According to Statista, Myanmar is the world’s fourth-largest producer of rare earths behind China, the US and Australia. The southeast Asian country sends most of its mining output to China for refining. Earlier this year, the authorities in Myanmar’s Kachin state, where most of its mines are located, suspended mining operations, which has led to stockpiling of the materials and a 6.2% price hike in the metals index, according to Small Caps.

Diversifying Supply

Other countries are making efforts to further diversify their supply. Australian miner Blackstone Minerals [BSX.AX] is one of several companies looking to tender a bid for a new rare earths mine in Vietnam, which could compete with the world’s largest, according to two companies cited by Reuters.

Africa is another region that could be key to the diversification of rare earth supplies, according to a December 2022 report from Brookings. The independent research institute argues that the continent is relatively under-explored and that most of its low exploration budget currently focuses on gold rather than rare earths.

Bannerman Energy [BMN.AX] in 2022 acquired a 41.8% stake in Namibia Critical Metals [NMI.V], owner of 95% of the Lofdal heavy rare earths operation, which contains dysprosium and terbium, two highly valuable heavy rare earth elements.

How to Invest in Disruptive Materials

Blackstone’s share price is down 14.8% year-to-date, while Bannerman Energy’s is up 42.8% and Namibia Critical Metals’ is down 46.7%

John Ciampaglia, CEO of Sprott Asset Management, recommends diversification when investing in mining stocks. In a March episode of Opto Sessions, Ciampaglia discussed the risks involved in mining investments, particularly the sector’s capital intensity and the long runway that projects often need to begin production. ETFs offering exposure to multiple miners across a diversity of minerals can offset the risk associated with any one project.

The Sprott Energy Transition Materials ETF [SETM] is one option for investors considering this approach; the ETF caps its exposure to any one given mineral at 25%. The fund is down 17.8% since it began trading in early February. Alternatively, the Global X Disruptive Materials ETF [DMAT] offers exposure “to materials that are core to powering disruptive innovations” in the energy transition. DMAT is down 18.9% since the start of 2023.

Both funds include First Quantum [FM.TO] in their top five holdings as of 17 October. First Quantum is a major copper producer that also produces nickel and cobalt. First Quantum’s share price is up 13.9% year-to-date.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy