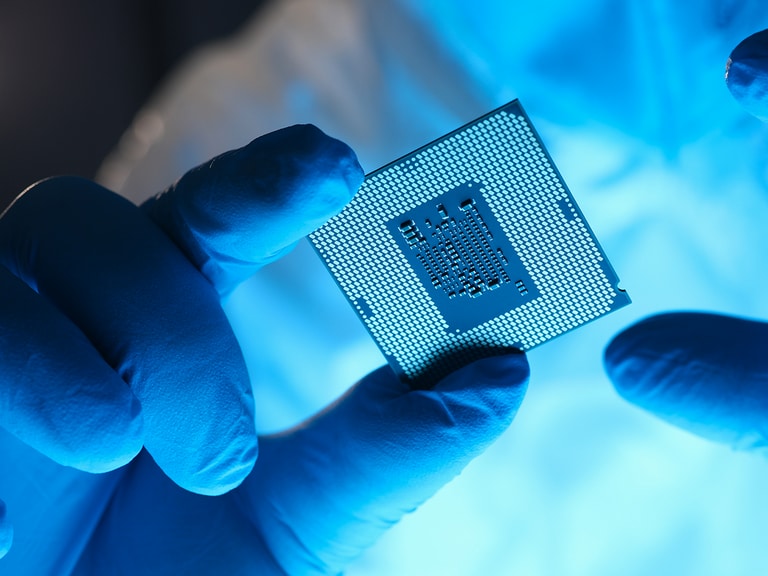

Samsung [005930.KS], the world’s second-largest semiconductor maker, is expected to finalise the location of its latest manufacturing unit in Texas soon, reported Reuters. With an outlay of about $17bn, the factory is being built in response to the crunch being felt globally.

Koh Dong-jin, Samsung co-chief executive and head of mobile, told a shareholder meeting earlier this year “There’s a serious imbalance in supply and demand of chips in the IT sector globally.” Dong-jin hinted at the time that the company may need to delay the release of its new Samsung Galaxy Note model, a move which was confirmed in August.

The Korean company trails Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company [TSM] the largest manufacturer with a 55% market share globally in semiconductors. The shortage has not spelt good news for the shares. The TSMC share price gained merely 2.8% in the year to 7 October, while the Samsung share price fell 10.9% in the same period.

The segment was caught in a vicious circle as purchasers were forced to downsize during the coronavirus pandemic. Now, having reduced capacities buyers are cutting revenue forecasts. Tesla [TSLA] share price and Volvo [VOLV-B] share price were hurt as they joined other auto companies to lowered earnings forecast as a result of the shortage. Electronics producers such as Apple [AAPL] share prices have also been affected.

“There’s a serious imbalance in supply and demand of chips in the IT sector globally” - Koh Dong-jin, Samsung co-chief executive

Why is there a shortage?

Tom Coughlin, fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and president of Coughlin Associates, told Fox Business that the semiconductor crunch is a consequence of the initial impact of the coronavirus pandemic. In the pandemic’s early stages, many companies reduced their orders of chips. With manufacturers simultaneously struggling thanks to pandemic-induced shutdowns and slowdowns, production capacity was reduced.

It takes longer to lower capacity than it does to increase it, so when demand recovered, supply has so far been able to keep up. Demand has also been driven by remote working practices and associated equipment that contains semiconductors.

The pendulum may, however, swing the other way.

Production plans

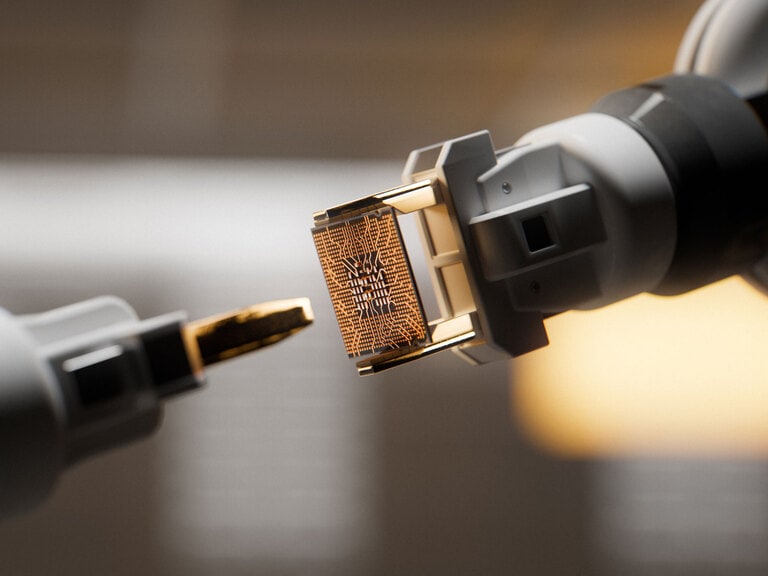

US president Joe Biden’s administration hopes to open up to eight chip producing facilities in the US. At the moment the country is heavily reliant on imports from Taiwan. In June, the US Senate voted for $52bn-worth of subsidies to kickstart US semiconductor production in the CHIPS (Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors) Act. It will now require approval from the House of Representatives.

Other countries too have jumped on it. South Korea has already approved $65bn to support the semiconductor sector. The EU has pledged to double its own contribution and Japan has pledged to match the outlay of other countries.

Intel [INTC] shares seemed to fumble to find new support as the company in September started construction of two new facilities in Arizona worth $20bn.

Outside the US and Taiwan, India is emerging as another potential production hub. The country is reportedly in talks with Taiwan over a $7.5bn investment deal that could see tariff reductions on semiconductor components come into effect by the end of the year.

Future prospects

The additional capacity will take time to become operational — each plant, according to Lisa Su, CEO of graphics chip and processor producer Advanced Micro Devices [AMD], takes at least 18 to 24 months. AMD, in contrast to Samsung and TSMC, has benefited from the shortage, with the AMD share price gaining 16% in the year to 7 October.

A recent report from IDC expects the industry to normalise by the middle of 2022. It even anticipates overcapacity from 2023 onwards, as the new fabs begin to come online from late 2022.

The timeline is consistent with Su’s predictions. Su told the Code Conference in Beverly Hills, California, that she expected the shortage to lessen in the second half of 2022, with the first half of the year “likely tight”.

Some might worry that this overcompensation in capacity could dent semiconductor prices in the long term. Mario Morales, group vice president of enabling technologies and semiconductors at IDC, doesn’t view this as a concern.

“The unit volume growth in many of the markets that [semiconductor producers] serve will… continue to drive very good growth for the semiconductor market” - Mario Morales

“The unit volume growth in many of the markets that [semiconductor producers] serve will… continue to drive very good growth for the semiconductor market,” he said.

IDC expects the semiconductor market to reach $600bn by 2025, at a CAGR of 5.3%.

There is, however, a danger that today’s clients could become tomorrow’s competitors. Amazon [AMZN] recently unveiled plans to produce its own in-house chips for its web and AI services. Tesla also unveiled its machine learning training chip at its AI day earlier this year, while Apple ended a long-standing relationship with Intel in favour of producing its own chips late last year.

Christopher Rolland, an analyst at Susquehanna, recently warned that semiconductor lead times had increased by six days to 21 weeks in August. However, he mentioned that there were encouraging signs for power management chips and optoelectronic components. Consulting firm AlixPartners estimates the impact on the global automotive industry at around $110bn in lost sales.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy