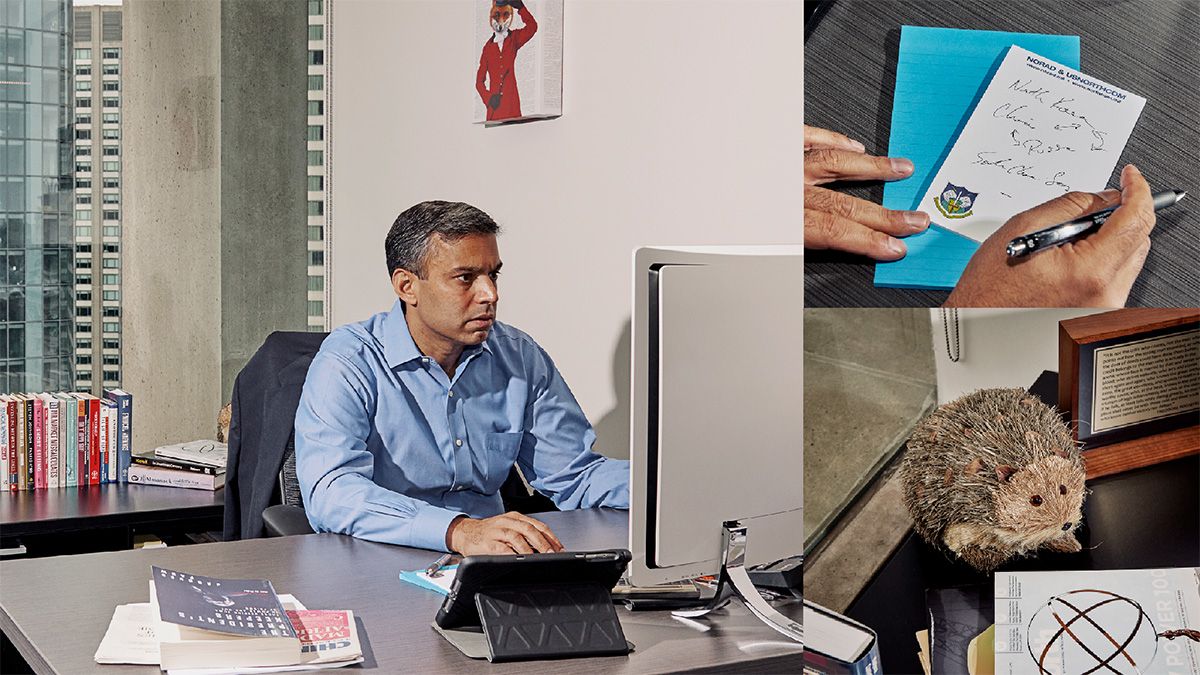

A picture of a fox hangs on the wall of Vikram Mansharamani’s office in Boston. It is, he says, a nod to a fragment of verse by the ancient Greek poet Archilochus: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

The parable relates to the distinction between those who are fascinated by the infinite variety of things and those who relate everything to a single, all-embracing system. The power of the hedgehog is down to his focus and central vision; he never wavers, never doubts.

The strength of the fox is in his flexibility and openness to experience; he’s more inclined to see complexity and nuance. “Generalists are far better than experts at spotting disruptive change,” says Mansharamani, who identifies as a fox but is more commonly known as a global trend-watcher, business commentator and “bubble spotter”.

“And yet we have become a society of specialists. The received wisdom is to turn to the hedgehog for answers.” Mansharamani came to prominence in 2011 with his book Boombustology.

One chapter looks at whether 10% growth rates in China are sustainable, pointing to a huge investment bubble that was about to burst. Most people laughed, and then stopped when his prediction came to fruition.

Boombustology was essentially a version of a class he taught at Yale University, where he lectured in business ethics and economic inequality. He didn’t expect the book to receive much attention.

“But in the final chapter, which I thought was a bit throwaway if I’m being honest, I took my methodology and applied it to a real-world problem,” he says. “My China prediction endorsed my methodology to lots of economics and business communities around the world.”

“I’m seeing a real loss of confidence in corporate boardrooms because of how Trump is behaving”

Since then he’s gone on to show others – including his students at Harvard University – how to use his multi-lens approach to manage risk, navigate uncertainty and peer into the future of crucial areas, from the global economy to housing and food.

The future doesn’t have to surprise anyone, he argues in a Harvard Business Review essay about managing uncertainty, as long as we adopt a generalist’s mindset.

“Corporations around the world have come to value expertise, and in so doing, have created a collection of individuals studying bark,” he writes. “There are many who have deeply studied its nooks, grooves, coloration and texture. Few have developed the understanding that the bark is merely the outermost layer of a tree Fewer still understand the tree is embedded in a forest.”

Or, as he tells Opto more directly, “It’s only those who view things with a single lens that miss the big white elephant in the room.”

Predictions

What are the most important developments to look out for over the next few years?

Mansharamani’s conversation, occasionally verging on hyperbole, is never less than engaging. “I get nervous about a lot of sectors,” he says, wasting no time in setting out his crystal-ball-gazing credentials.

Some of the structural trends he thinks will be “unstoppable” are currency wars, with investors rushing for non-printable currencies such as gold and Bitcoin, superbugs and oil production.

But there are two more urgent developments that Mansharamani is most keen to highlight.

“The US-China trade war is having a massive impact on the profile of decision making in Fortune 500 companies,” he says. “Trump has a unique way of negotiating, to put it mildly, and it’s very hard to read.

“I advise a lot of prominent CEOs in America with their business decisions,” he continues. “Again and again, I’m seeing a real loss of confidence in corporate boardrooms because of how Trump is behaving. CEOs are starting to feel paralysed. And it’s having a multiplying effect.”

Mansharamani says the rise of Trump is a symptom, not a cause, of a much wider problem.

“Some people might find this controversial, but let’s not fool ourselves,” he says. “Globalisation plays a part – certainly, we’re seeing the re-emergence of a strong man representing the needs of the white man left behind. But there are other, underappreciated factors at play; for example, manufacturing jobs lost to technology.”

The other development – or lack thereof – concerns India. “The country is completely misunderstood,” he says.

In typically forthright manner, he continues: “It’s based on a belief that the middle class will grow and spend like the Chinese did. But I believe the model of putting cheap mass labour from large countries into the manufacturing industry, earning them a decent income and increasing their spending power, is broken. Technology and automation has disrupted that model. The unskilled illiterate Indian is competing against a highly intelligent machine. There can only be one winner.”

“The idea that India will be the next China is simply wrong.”

To support his argument, he cites the numbers of Starbucks in the respective countries: China has about 3,000 stores, with a new one opening every 15 hours; while India has about 100 stores, with just a single new opening a week.

“People say to me, ‘But India drinks tea!’ I say back to them, ‘But so does China!’ There’ s a certain amount of revisionism at play. And I can’t see Indian growth coming to fruition.”

Connecting the dots

Soon after British colonial rule in India ended in 1947, Mansharamani’s parents moved to the US. “They lived just outside Karachi but, when the Brits drew the line, found themselves on the wrong side,” he says.

The family moved around a lot. Mansharamani was born in Queens, New York, but he spent the majority of his childhood in suburban Landing, New Jersey, where he went to public school.

“We were a lower middle-class family,” Mansharamani says of his upbringing. His mother was a dietician, his father a car mechanic who started his own business.

“He was pretty entrepreneurial,” he says. “Maybe that’s why I started to develop an interest in the business world.”

His experience was varied and his rise fast. He won a scholarship to the Blair Academy. “The first time I really had my eyes opened to the world,” he says.

He interned at the US embassy in Beijing and on the trading floor of Bear Stearns. He went on to work on Wall Street after gaining a degree from Yale and later completed a PhD in innovation at MIT.

“People asked, ‘What is that?’ And, really, it’s a bit of everything: politics, economics, psychology and many other things. Academically, I was like a kid in a candy store.”

The thread uniting all off his various endeavours, he explains, is the desire to be exposed to “the broadest cross section of new ideas as possible”. No surprise, then, when he accepted an invitation as one of a small group of “thought leaders” to spend time with the US Air Force and military last summer.

“If I understand the threats they perceive, it will help me become a much better investor and appreciate risk in a different light,” he says. “And in a better light than just by reading, say, Bloomberg or The New York Times. When hurricanes Harvey and Maria hit Puerto Rico, the risks had been elevated to me months before, because of the time I spent with the military.”

It is through widespread experiences such as these that have formed his blueprint for how to spot bubbles or look for investor opportunities.

“I have some specific indicators. I worry when I see people borrowing in the face of overcapacity. I look for signs of overconfidence or hubris. For example, when countries start chest-thumping by putting up tall buildings, something is usually about to go wrong. Political manipulation is another factor I look out for.”

Another important indicator, he says, is whether the cab driver is talking about it yet. “When the amateurs are on to something, there aren’t many people left to affect."

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy